WHEN THE HONORABLE George Z. Singal ’67 presides over naturalization ceremonies in U.S. District Court in Portland, the new citizens hear a story they were not expecting from the man in the black robe high on the bench.

Looking out over families from Maine’s immigrant communities, Singal holds up his citizenship certificate and says, “Just like you, I was a refugee, too.”

Recipient of the 2021 Alumni Career Award, the Alumni Association’s highest honor presented to graduates with outstanding achievements in their life work, Singal personifies what it means to be an American.

“I keep my citizenship document in my desk in my office and look at it periodically,” he told me recently. “It is that important. What a country we live in.”

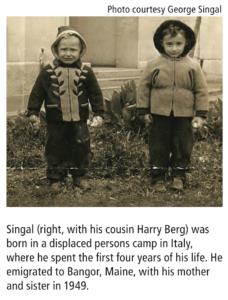

When Singal was born in 1945, his mother and older sister were awaiting an opportunity to enter the United States from a displaced persons camp in Italy. His family had left their home in eastern Poland in 1939 amid rumors the Nazis were about to invade their village and round up Jews to be shot. His mother urged the family to leave, but many stayed.

“I lost almost all my aunts and uncles, both sets of grandparents — all the members of my family who were still there,” he said in a U.S. Courts video titled “Pathways to the Bench.”

Singal’s mother, father, and four-year old sister, Judith, fled to the surrounding forest where they spent four years with a group of guerilla resistance fighters, struggling to stay alive and ahead of the Germans. When the Russians liberated the region in 1944, the family returned to their village, only to find the homes occupied and the town awash in anti-Semitism.

AGAIN, THE FAMILY resolved to flee, but Signal’s father died before they could leave. Five months pregnant, Malka Singal took her daughter from Poland through Austria and over the Alps, riding in the back of an open truck, to Italy, where George was born four months later in a displaced persons camp.

AGAIN, THE FAMILY resolved to flee, but Signal’s father died before they could leave. Five months pregnant, Malka Singal took her daughter from Poland through Austria and over the Alps, riding in the back of an open truck, to Italy, where George was born four months later in a displaced persons camp.

“No country was open to refugees,” Singal explained in our conversation, adding every country wanted refugees to be accepted someplace else. “We stayed four years at the refugee camp waiting for an opening.” Finally, Malka was able to locate distant cousins living in Bangor, Maine, who were willing to sponsor the family, meaning they could guarantee the immigrants would not require public benefits. The family boarded a troop ship bound for New York and landed “literally with nothing,” and knowing no English. “My mother spoke five languages, but not English.”

Judith went right off to school, followed by her younger brother when he was old enough. Upon graduation from Bangor High School, Singal entered the honors program (now the Honors College) at the University of Maine.

“I learned more at the University of Maine than at any other time in my life,” he said. “I learned how to think. I left with the gift of being analytical.”

Praising the diversity of a liberal education, he recalled that in the honors program, “You experienced everything – philosophy, science, language, economics – not to make you an expert in one thing, but to expose you to different thought processes.”

Singal graduated summa cum laude in 1967, with a degree in international a”airs and memberships in several honorary societies including Phi Kappa Phi and Phi Beta Kappa. He envisioned entering Tufts University to study international relations but was persuaded to apply for law school by his honors advisor, Prof. Robert Thomson, and Maine Law School Dean Edward Godfrey, who assured him he could still practice diplomacy with a law degree. He was not only admitted to Harvard Law School, but also won a Felix Frankfurter Scholarship.

“My mother was amazed that in this country you could go as far as you wanted, free for the most part,” he said in the U.S. Courts video. “Public schools took you right through high school, and then I went to state university and ended up with a scholarship to Harvard Law School.”

“My mother was amazed that in this country you could go as far as you wanted, free for the most part,” he said in the U.S. Courts video. “Public schools took you right through high school, and then I went to state university and ended up with a scholarship to Harvard Law School.”

A cum laude graduate of Harvard in 1970, he attributes his ability to compete successfully with graduates of Ivy League colleges to the quality of his undergraduate education at UMaine. While many of his classmates began their careers at large, urban law firms, Singal decided to practice in his hometown. “I wanted a different style of law,” he explained, calling Bangor a wonderful place to grow up. “I wanted to represent people rather than companies.”

HE RETURNED TO Maine with his wife, the former Ruthanne Striar of Brookline, Massachusetts, who was studying social work at Simmons College in Boston when they met.

He joined the firm Gross, Minsky and Mogul and had been practicing 30 years when he received a call from Maine Congressman John Baldacci ’86 asking if he was interested in becoming a federal judge. U. S. District Judge Morton Brody had passed away unexpectedly, and President Bill Clinton was seeking to replace him.

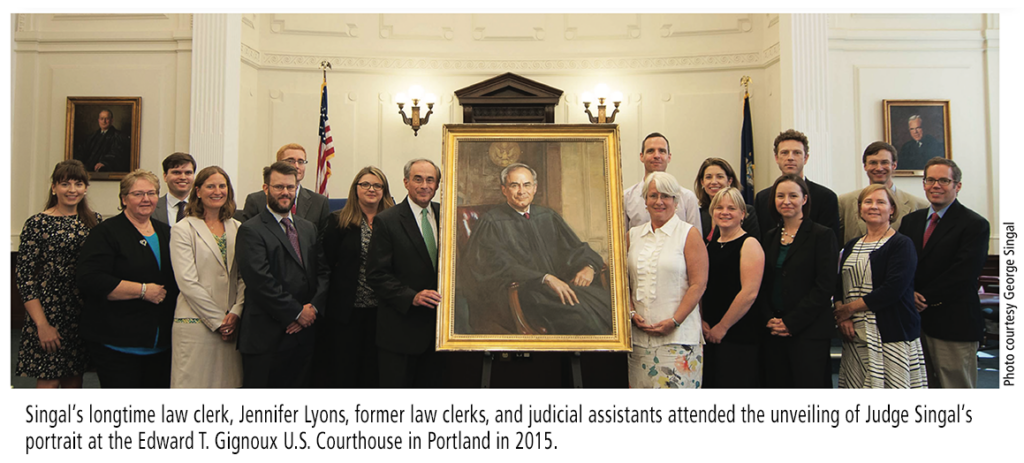

Singal’s longtime law clerk, Jennifer Peacock Lyons, Esq., remembers the day in 2000 when he walked into the federal court offices in Bangor and announced he was likely to be appointed a U.S. District judge and was going to need a clerk. Was anyone interested? As Brody’s clerk, she had known Singal as a lawyer.

“You never know when that transition from one side of the bench to the other will occur,” she reflected recently, noting she is “closing in on 20 years” of working with Singal, first as a term clerk and then as career clerk, after he became chief judge in 2003. He assumed senior status in 2013, and, in 2019, U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts appointed him to a seven-year term on the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, one of 11 judges in the nation who provide this specialized volunteer service relating to foreign intelligence gathering.

“It is intellectually rewarding and challenging,” Lyons said of her work with Singal. “I am impressed with the breadth of issues he is willing to take on in his portfolio of work.” Describing him as a generalist, she said he is comfortable with all kinds of law. “He keeps up to date on everything. He is always looking for ways to improve the legal system. He definitely believes he has something to learn from everyone.”

In 2015, Lyons told those gathered for the unveiling of Singal’s portrait at the courthouse in Portland, “His frequent use of the phrase ‘educate me’ in all its variations holds many lessons. He genuinely believes his own education is never complete.”

Dr. Melissa Ladenheim, Associate Dean of the Honors College, quoted those words in nominating Singal for UMaine’s Alumni Career Award. She recalled recently that, as a lecturer and recipient of the Abram Harris Award, he has been an inspiration for students in the Honors College who often don’t see themselves as fitting in. “Someone coming into your life who says, ‘you belong, you have what it takes,’ is powerful — transformative.” Her nomination recognizes not only his illustrious career, but also “his commitment to learning as a lifelong endeavor” and “the steadfast and humble person he has remained as he has achieved great success.”

Her thoughts are echoed by Singal’s colleague at Gross, Minsky & Mogul, Edward W. Gould, who writes that in addition to his great legal skills, “I am nominating him because of the person he is and the example he has set for the University of Maine community and for all of us.”

Seen as a mentor for clerks and other lawyers launching their careers, Singal provides an example for balancing dedication to his profession and to his family and community. Father of two grown children, Jessica and Samuel, with four grandchildren, he puts family above the all-encompassing demands of his work. “I was told ‘Law is a jealous mistress’ but I have dinner with my family every evening,” he said in our conversation, adding he also encourages staff to spend time with family. “Family is critical.”

Reflecting on 20 years as a judge, Singal sees significant increases in the complexity of federal laws and in the amount of time devoted to drug cases. “It’s a real epidemic in Maine,” he said, calling the shift to more and more lethal drugs a “horrendous, terrible situation.”

WHEN ASKED TO recall high points in his career, Singal cited expressions of appreciation from people whose lives were changed by his work as a lawyer and as a judge. He remembered receiving a Christmas card from an abused wife who, after his successful defense, was acquitted of murder in the death of her husband. “First, the jury had to be educated on what it means to be a battered woman,” he said. $e card pictured the woman, her children and their dog with this note: “We named the dog George.”

“I saved a life. I saved children’s lives,” Singal said. “$at’s what it means to be a lawyer.”

Another person was grateful for his wisdom as a judge. Singal was apprehensive when a man approached him as he was leaving the grocery store in Bangor, identifying himself as one who had come before him in criminal court. “You lectured me,” he said, “and I remembered that.” He wanted the judge to know he had served his time and turned his life around.

“Now that’s satisfying,” Singal said.

During naturalization ceremonies in Portland, Singal asks the restless immi-grant parents to look at the children sitting next to them.

“I want to tell you, your child can be sitting here,” he declares from his seat on the bench, relating his own immigrant experience where “every door is open” and all you have to do is get an education and work hard.

“They perk up. Now they’re listening,” he told me. “They understand what is possible that is not possible in most other countries. They are shocked.”

Reluctant to comment on the politically charged situation facing immi-grants today, Singal is adamant about the future of democracy. “Is democracy at risk?” I asked. “Absolutely not,” he replied. “Democracy has a long history. Americans have fundamental beliefs. This country has a deep foundation, like frost in the ground in Maine.” M