By Nina Mahaleris ’20

Author’s note: This article references Jordan Marie Daniel using they/them pronouns, as the subject prefers.

JORDAN MARIE DANIEL ‘11 (full name: Jordan Marie Brings Three White Horses Daniel) hadn’t exactly intended for a life in the limelight. Daniel, who belongs to the Kul Wicasa Oyate, also known as the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe in South Dakota, was a shy child, unlikely to draw attention to themselves.

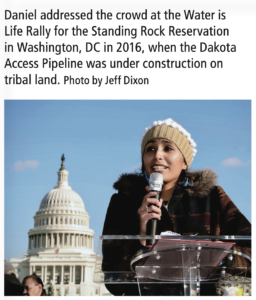

But fate had other plans. The fourth-generation Indigenous runner garnered national attention in 2019 for running the Boston Marathon with the letters “MMIW” painted down their legs with a large red handprint covering their mouth.

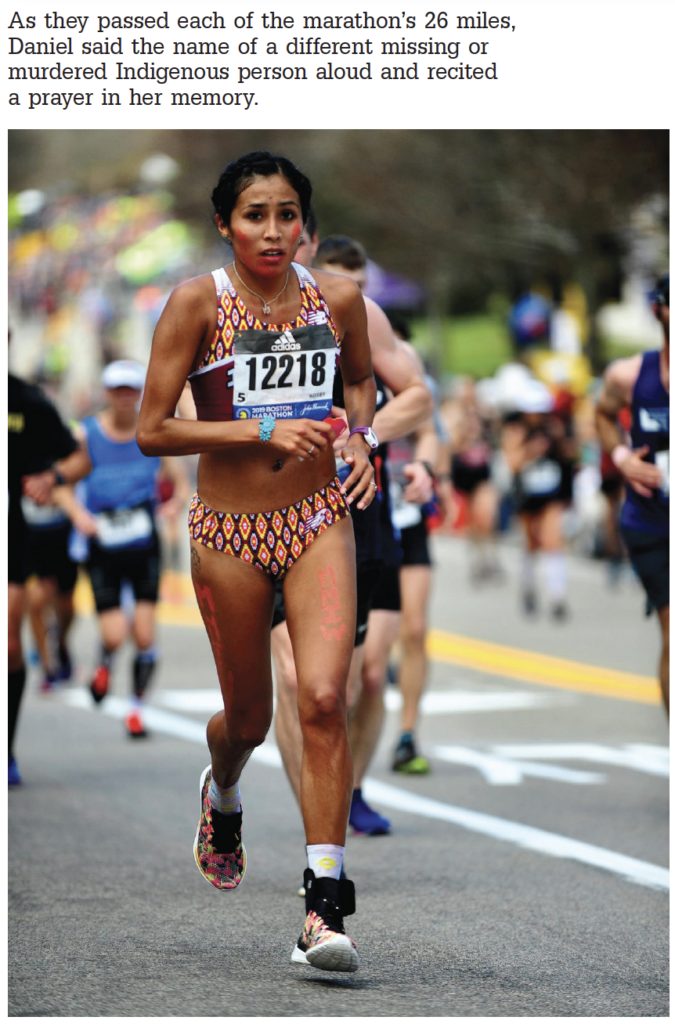

As they passed each of the marathon’s 26 miles, Daniel said the name of a different missing or murdered Indigenous person aloud and recited a prayer in her memory.

Daniel said they wanted to raise awareness for the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women movement, which is promoting public awareness of a crisis plaguing Native communities across the nation: the murders and disappearance of Indigenous women and girls.

They did so quietly — no soap box or bullhorn involved. Daniel wanted to honor those lost while bringing attention to the underlying systems that allow violence against Indigenous people to persist with little national intervention.

In 2016, there were 5,712 cases of missing American Indian and Alaska Native women and girls, according to the National Crime Information Center. Fewer than 120 of those were logged into the U.S. Department of Justice’s missing persons database.

“I didn’t want to purposely make a spectacle about it,” Daniel told Indian Country Today in 2019. “I wanted this run to be for our stolen sisters and my lala [grandfather]. It was my way to give these womxn* a platform to be seen, heard, and remembered.”

*This alternative spelling of “women” is taken as presented in the article from which Daniel’s quote appeared.

That run helped shape the future of Daniel’s work as an advocate for Indigenous rights.

“I’ve always known from a very young age, eighth grade, my dream was to go to D.C. and be an advocate and lobby on ‘The Hill’ and help [implement] this systemic change that we need for Indigenous peoples to be heard and respected and included,” Daniel, 33, said.

“I’ve always known from a very young age, eighth grade, my dream was to go to D.C. and be an advocate and lobby on ‘The Hill’ and help [implement] this systemic change that we need for Indigenous peoples to be heard and respected and included,” Daniel, 33, said.

While they credit family — specifically their mother and grandfather — for modeling a community-oriented mind-set, it was Daniel’s own experiences with injustice that inspired them to become an activist.

One of the most impactful if these encounters happened not long after Daniel moved from South Dakota to Farmington, Maine, in 1996. Daniel’s father took a job as a psychology professor at the University of Maine at Farmington, sending a young Daniel — then nine years old — more than 1,500 miles away from everything they’d known.

“It was a big culture shock,” Daniel said. “I really struggled, it [made] me question my identity, it made me ashamed of who I was because at the time I moved there, I was the only kid of color.”

In middle school, Daniel experienced a hate crime for the first time. As they were walking with a white friend, a group of white teenagers drove by, jumped out of the car and started threatening the pair. The teens had brass knuckles, chains, and a pocket knife with them.

After urging Daniel to run away, their friend was beaten up by the gang of teens.

Between 1997 and 2001, there were just under 200 incidents of hate crimes reported in Maine, according to the state’s Uniform Crime Reporting data-base. However, this is likely an underrepresentation, due to officers mishandling cases or victims choosing not to report the crime out of fear.

Such was Daniel’s experience. “We tried to get justice out of it and nothing happened,” they said. Th police chalked it up to ‘kids being kids.’

The attack, while horrific, allowed Daniel to see what the world was really like. They began to notice injustices in other areas of their life, too. “Even though I was kept in a little bubble … and I’m sure my parents tried to shield me from that … I had an incredible perspective at a really early age,” Daniel said.

Seeing injustices occurring both outside of and within their own communities motivated Daniel to become an advocate for change. Though it wasn’t until adulthood that Daniel understood the true extent of the racism they’d endured as a child. “It wasn’t until my trip back to Maine last year during the pandemic that it finally all clicked together.”

As America reconciled with its own racist history in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, Daniel came to a similar realization.

Driving around with their family, memories of growing up in Farmington flooded Daniel’s mind. They thought about all the times they experienced prejudice without even realizing it.

It made sense why they weren’t always allowed to go over to their friends’ houses, or why sometimes the parents of some-one Daniel was dating acted awkwardly or disrespectfully towards them. “[There were] parents who clearly didn’t like me and I had no idea what that meant, I had no idea why … I just wanted to fit in and I definitely was stick-ing out like a sore thumb,” Daniel said. “It was a very alienating experience.”

As a Native brown kid growing up in rural Maine, Daniel endured these micro-aggressions for years, though it would be nearly two decades until Daniel really understood how those experiences shaped their identity and future.

Reclaiming their indigeneity

As a Native American person living in a predominantly white state, Daniel’s struggles accepting their Native roots persisted in college. Their community, family, and tribe were on the other side of the country. Around the same time, their grand-father fell sick with cancer.

Daniel felt stuck between two conflicting worlds; one part of themselves desperate to #t in, ashamed of their brown skin. Another, deeper part, begging to embrace their indigeneity. “I was really struggling to #t in this institution,” Daniel said.

Professor gkisedtanamoogk, a Wampanoag educator and then-faculty member in the Native American Studies program, noticed Daniel’s troubles. He suggested they visit the neighboring Penobscot Nation.

Though they initially felt like an imposter for attending another tribe’s event, Daniel said the Penobscot Nation community helped them recover their Native identity. “It felt like the community I [had] back in South Dakota.”

“Right then, that was kind of like a reclaiming of who I am. That just reassured me: you’re supposed to be Native; you’re supposed to be a Lakota woman. This is your path.”

Other Native American educators at UMaine — particularly Maureen Smith, Darren Ranco, and Bill Whalen — also helped Daniel reconnect with their Indigenous roots. “I really relied on them to have that Indigenous connection somehow,” Daniel said.

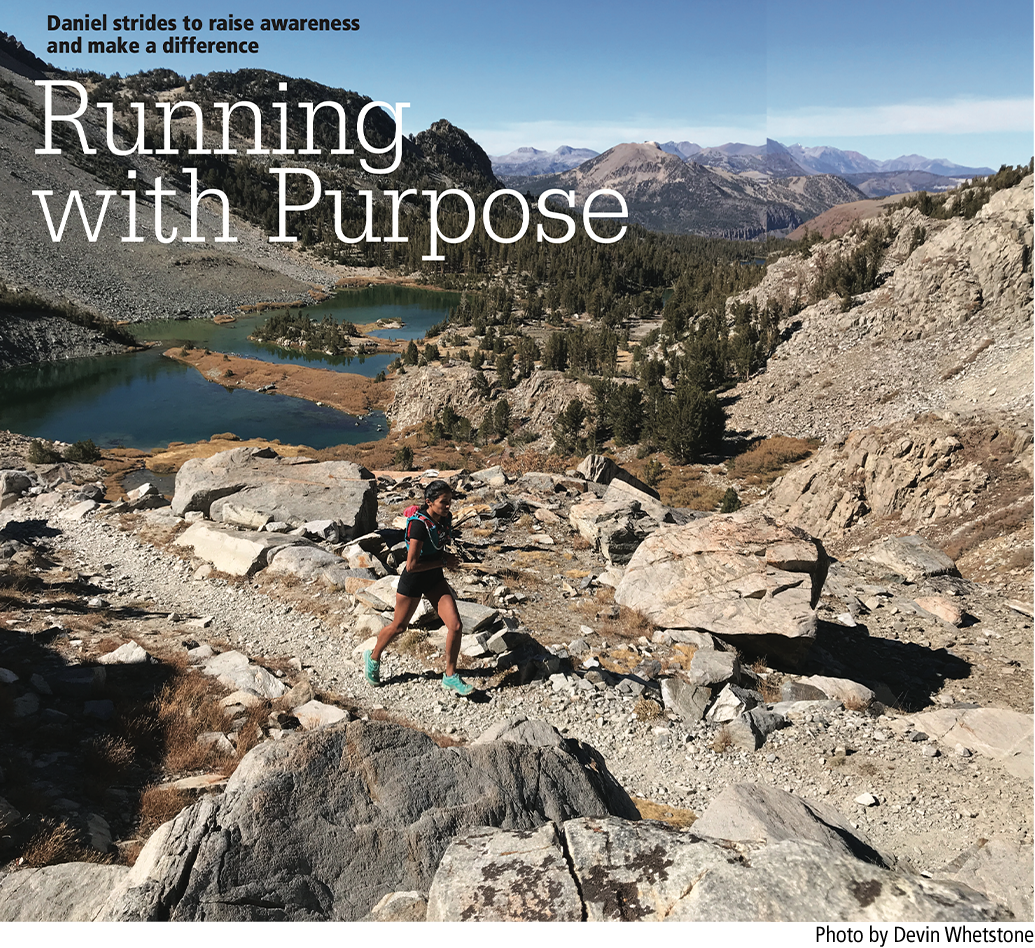

Daniel also found a sense of purpose and belonging through running. “[Running] was about how you show up to the start line and finished — not about the color of your skin. It was a community I felt accepted in,” Daniel said in their online biography.

Running is literally in Daniel’s blood.

Their mother, Terra Beth Brings Three White Horses Daniel, was a sprinter who trained for the 1988 Olympics. Daniel’s grandfather, Nyal Brings Three White Horses, was a well-known runner credited with achieving a 4:10 mile in the 1950s.

He was also the one to bring Daniel on their first run at the age of 10.

“Running for me has been about culture, legacy, history, and continuing this tradition of our family. It’s connected me so much to my family and our community and also transformed into being about representation of a Native athlete,” Daniel said in an interview with iRunFar, an online running publication, earlier this year.

Daniel continued to run through high school and college. They placed in the top ten in the 1,600 and 3,200- meter events while competing for Mt. Blue High School and helped the team secure a cross country state championship title in 2002.

Daniel also secured top spots in numerous meets for the UMaine Women’s Track and Field team. During the 2008–2009 season, Daniel placed third in the 3,000 meter at the Maine Open, first in the 5,000 meter against the University of New Hampshire, and fourth in the 5,000 meter at the University of Massachusetts.

The previous season, Daniel competed in the America East Outdoor Championships, placing ninth in the 5,000 meter with a time of 18:17:40.

Daniel graduated in 2011 after taking two redshirt seasons — a period of time in which a student-athlete doesn’t compete — for cross country and indoor track.

The sport seemed to become more intentional for Daniel post-college, however, and Daniel soon found new ways to connect their two passions: running and advocating for social justice.

“Aside from being a competitive runner, I’ve found a new purpose in my running,” Daniel wrote in a 2019 piece for Global Sport Matters. “I’m running for justice, to raise awareness of an epidemic and national crisis: missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. My body is a messenger in this journey and I paint it on my body to honor, remember, and recognize those stolen from our communities.”

Finding their voice

The outspoken persona Daniel exudes as a community organizer didn’t exactly come naturally to them.

In 2010, they were accepted to the Maine National Education for Women Leadership Program, — a program of UMaine’s with the Margaret Chase Smith Policy Center designed to help empower young women in leadership roles.

Knowing they would have to speak publicly and network with high-ranking people, Daniel nearly turned down the opportunity. “I almost declined it because I knew I would have to speak, but my dad encouraged me to do it,” Daniel said.

Knowing they would have to speak publicly and network with high-ranking people, Daniel nearly turned down the opportunity. “I almost declined it because I knew I would have to speak, but my dad encouraged me to do it,” Daniel said.

“‘You’re going to have to learn how to network and how to sell yourself and sell the things you’re fighting for,’” he said.

The program was intimidating, Daniel remembered, but it forced them out of their comfort zone. “I harnessed a lot of [the skills I learned there] as I transitioned into being a community organizer and advocate,” Daniel said.

In 2013, Daniel fulfilled their dream of moving to D.C. to work with the National Indian Health Board (NIHB). In that role, they worked on various initiatives to improve healthcare for Native communities.

Shortly after, Daniel left the NIHB to intern with U.S. Representative Chellie Pingree, where they learned what working on “The Hill” really meant. Daniel became disheartened by the lack of Indigenous representation in D.C.; they wanted to work with communities directly, not from inside a delegate’s office.

Leaving politics behind, Daniel took a position with the Administration for Native Americans, working closely with Native communities and implementing change from the ground up. “As I’ve been in these advocate spaces, I’m truly motivated and inspired by community.”

Looking Ahead

Now, Daniel stays as busy as ever.

Daniel is currently producing The Sacred and the Snake, a documentary featuring three Indigenous activists whose lives and communities were deeply impacted by the Dakota Access Pipeline.

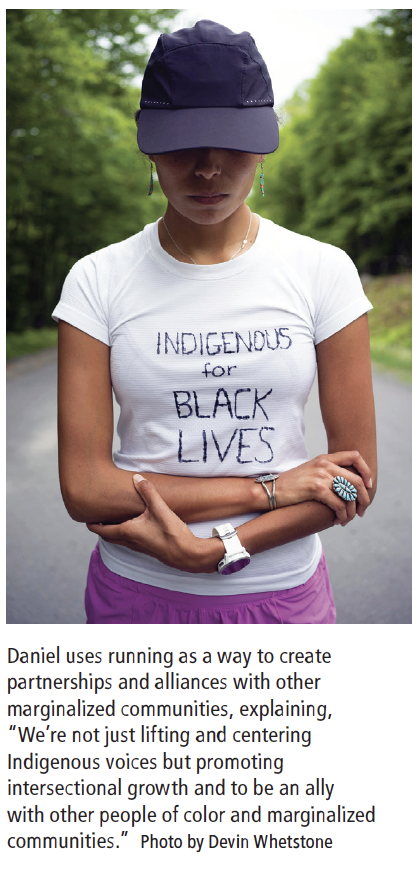

Daniel is also the founder, executive director, and organizer of Rising Hearts, an Indigenous-led grassroots group dedicated to elevating Indigenous voices and promoting racial, social, climate, and economic justice.

Recently, Daniel co-directed a short film featuring Lydia Jennings, Ph.D., a self-proclaimed “Native soil nerd” and Indigenous runner who ran 50 miles in prayer to pay tribute to 50 Indigenous scientists and knowledge keepers.

Advocacy work, particularly crisis awareness, is not easy on the heart but Daniel wants to share both the positive and negative things happening in Native spaces.

“I don’t want people to always think that a crisis is always happening in Indigenous communities,” Daniel said. Speaking out against injustice is import-ant work that needs to happen, they said. “[But] I would rather be focusing on the resilience and the beauty and I feel like sometimes that gets overshadowed a lot, sadly.”

By doing this work now, Daniel hopes that one day their descendants will not have to su”er the same way Native people have in the past and present. “I don’t want them to inherit this intergenerational trauma. I’m doing this work to keep our next generation safe.”

Find out more about Rising Hearts and Daniel’s other projects at https://www.jordanmariedaniel.com.

To learn more about The Sacred and the Snake documentary, click here. M