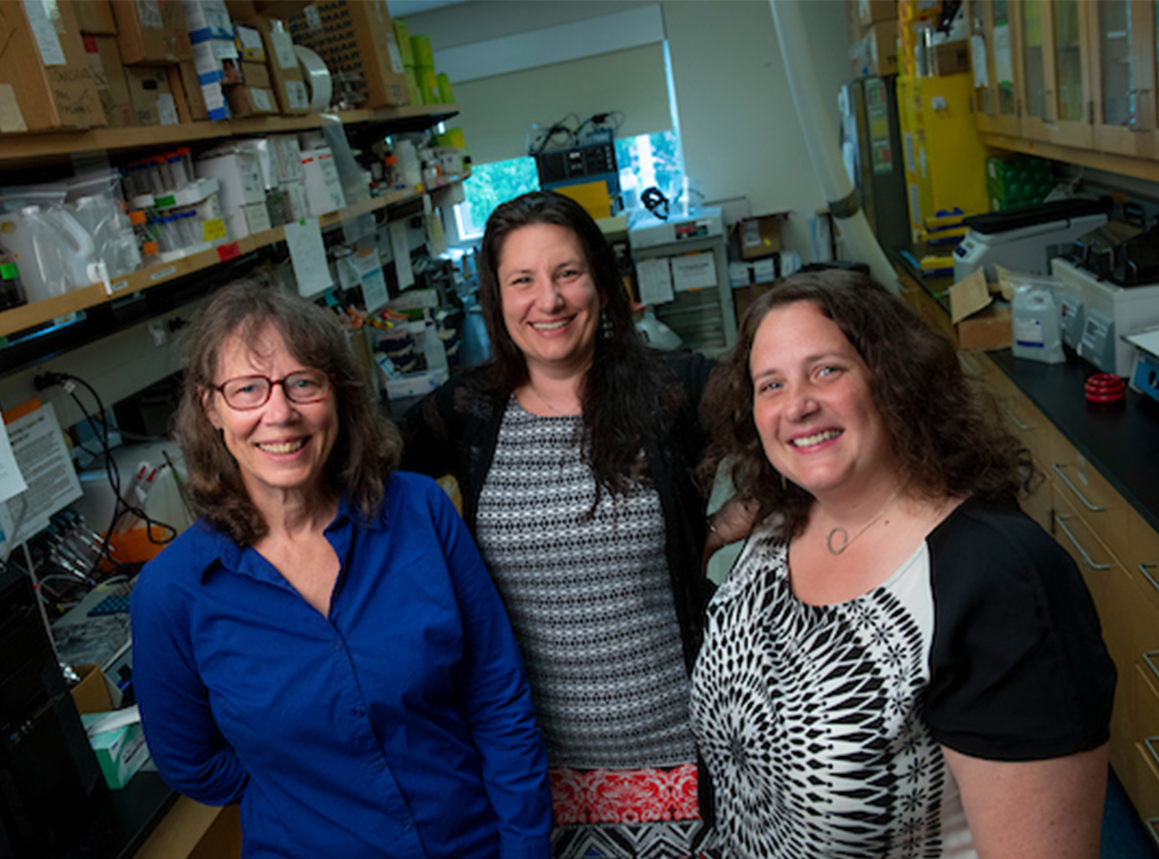

Black Bear alumni, faculty, staff, and students are among Maine’s most productive innovators and entrepreneurs. This month’s edition of our “Innovators of UMaine” series showcases Neuright, a Maine-based biotech company co-founded by Kristy Townsend ‘02 Ph.D. (above right), and Magdalena Blaszkiewicz ‘19G, Ph.D. (center). The company is developing a medical device that will aid in the diagnosis of peripheral neuropathy, specifically the small-fiber neuropathy that can manifest through sensations such as pins-and-needles, numbness, and tingling. Peripheral neuropathy is common in patients with diabetes and those who are undergoing chemotherapy treatments, but the condition also occurs without obvious cause, and is stubbornly difficult to diagnose, Townsend and Blaszkiewicz say. The pair, working with collaborators at UMaine including Rosemary Smith, professor of electrical and chemical engineering (above left); Leonard Kass, associate professor of biological sciences; Nuri Emanetoglu, associate professor of electrical and computer engineering; and Ali Abedi, professor of electrical and computer engineering, have developed a microneedle electrode array that’s designed to record nerve activity. The goal is to create a functional diagnostic tool for aging and diabetes-related small fiber neuropathy.

Neuright evolved out of Blaszkiewicz’s Ph.D. research in the Townsend Lab at UMaine. The founders developed a plan for commercialization through UMaine’s MIRTA Accelerator program, and Neuright is headquartered at the Upstart Center for Entrepreneurship. Now based at Ohio State, the Townsend Lab maintains close ties with research collaborators at UMaine and Neuright’s founders say they are committed to growing the company in Maine.

This month, Bear Tracks had a chance to catch up with the founders, who are wrapping up preclinical trials in mice (all conducted at UMaine with strong research support from undergraduate students) and preparing for clinical testing in humans.

BT: What was the inspiration for your innovation?

KT: “This really came out of Magda’s Ph.D. research in my lab when I was faculty at UMaine. We were investigating the nerves in the adipose tissue, or fat tissue, that’s under the skin, and how those change with obesity, diabetes, and aging. We found that the nerve density is reduced, indicating probable nerve death and neuropathy in the adipose. We wanted a tool to be able to measure functionally, that the nerves were not as active as they should be, and then look at what implications that would have for metabolic health, and health of our fat tissue, but there was just no way to do it. It’s really hard to measure the function of the nerves in adipose — we can look at molecular markers, and that sort of indicates how healthy and how functional they are, but they’re indirect measures. We assembled a team at UMaine and started to get prototypes together and began recording. At the time, we didn’t think this was something that could be commercializable, or that it should be, but we were invited to take part in the first cohort of the MIRTA accelerator program at UMaine, and we did. What we learned was that our research needed to measure the function of these nerves in patients with neuropathy matched a clinical diagnostic need, and by developing a commercialization strategy and a spin-off company, we could help the technology be developed and hopefully become useful for patients.”

BT: How will your innovation impact people?

MB: “Through [customer discovery in] the MIRTA program, we came to understand that physicians who are trying to diagnose small-fiber peripheral neuropathy are struggling with the tools available. They’re having to use multiple tools and put patients through a battery of testing to get a final diagnosis, which is often a diagnosis of exclusion. For a patient who is experiencing pain, numbness, tingling and loss of sensation, the process is harrowing and doesn’t always result in a definitive answer. Some patients spend years trying to get a diagnosis, and early-stage cases can be missed because existing methods can’t detect reduced nerve function. Right now, there is no cure for peripheral neuropathy, but there are intervention measures that could slow the progress of the disease if it can be identified sooner. This technology would help patients get to a diagnosis faster and pursue treatment earlier. While clinicians will use the test first and make the diagnosis officially, we’re trying to be very patient centric in our design because it’s patients who want and need this technology to reach a more reliable answer even if there isn’t an easy treatment.”

BT: What are your goals for your innovation? Where do you see it five years from now?

MB: “Five years from now, we hope to have been cleared by the FDA for marketing so we can have this device in clinics being used by physicians. We want to get the first phase of our concept out there as a diagnostic tool, but then continue evolving the platform. We see the device potentially being used to provide treatment or investigate whether certain treatments would work. We also hope to be able to collect neurological signature data from patients to better understand what’s causing these neuropathies. Those data could help other researchers come up with more targeted therapies for the different types of peripheral neuropathy. So, as we’re getting the first iteration of the idea commercialized and out the door, we’re also going to be working on the next evolution to focus on treatment and understanding the cause of the disease by using our microneedle array to collect data that will help us get to biomarkers and biosignatures.”

BT: How do you see innovation in biotech benefitting Maine?

KT: “I’m also on the board of directors for the Bioscience Association of Maine and we recently undertook a big data collection effort around what the biotech and bioscience space looks like in Maine. This is a growing sector of Maine’s economy and we have a lot of talent that can be leveraged. Not just for academic spin-out companies like ours, but attracting people to come to Maine and to collaborate with universities or collaborate with other small biotechs. Maine is a state where it’s cheaper to set up shop, but you still have the proximity to Boston. We’re committed to keeping Neuright in Maine not just because we have strong connections here and we love Maine and want an excuse to come back, but because it really is a good place for a small biotech business. We also hope to have our device manufactured in Maine because it has all the infrastructure for medical device manufacturing. I was born in Maine, I was raised in Maine, I’m a Maine proponent. After seeing the data, I do think Maine is a great place to grow or start or move a small company like ours.”

NOTE: The “Innovators of UMaine” series is supported by a grant to the Alumni Association from the Maine Technology Institute.