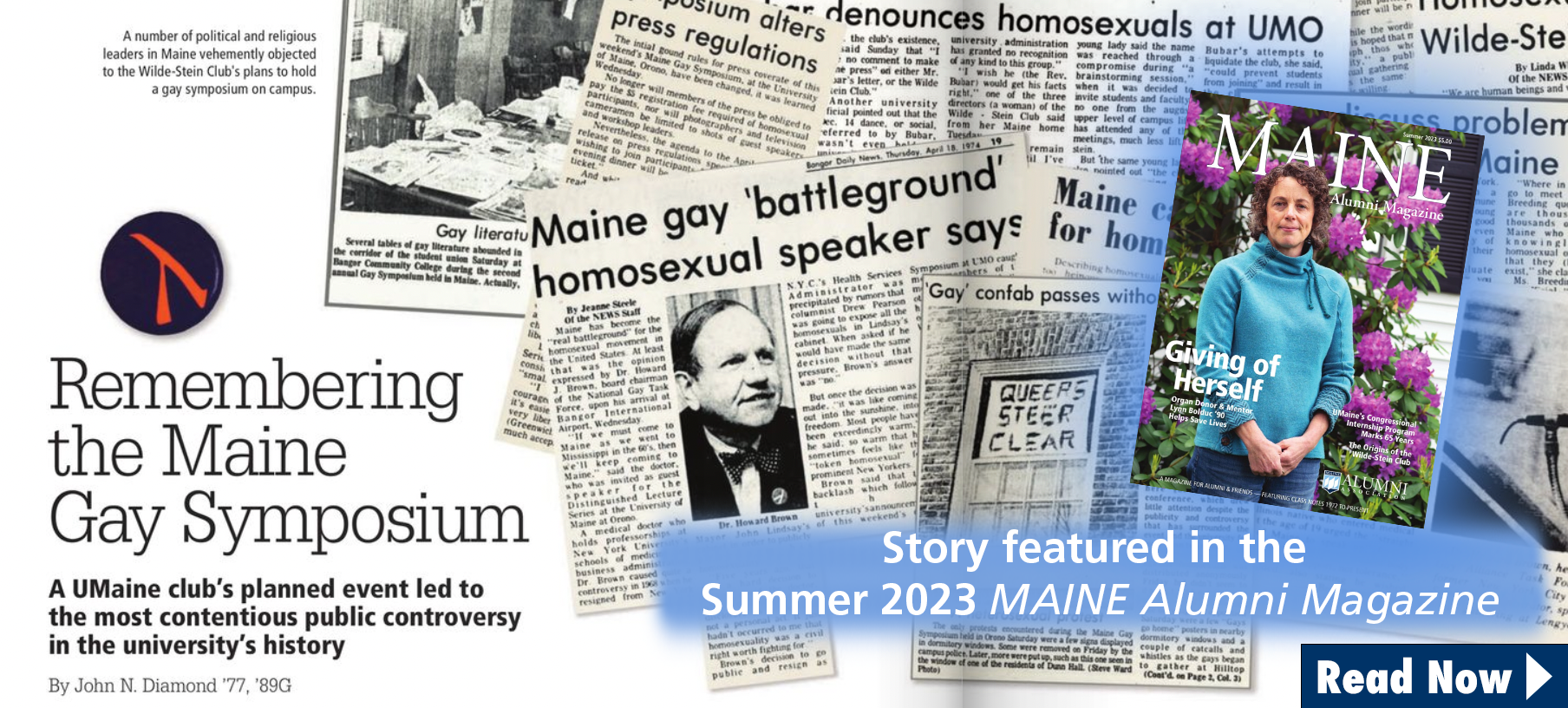

A UMaine club’s planned event led to the most contentious public controversy in the university’s history

[To view story in the MAINE Alumni Magazine, click here]

In 1973, a week or so into his freshman year at the University of Maine, Dan MacNaughton spotted a flyer in the Hilltop Commons dining hall.

U of Maine Gay Students

Feel like you’re the only gay on campus?

You don’t have to be alone any longer.

There’s a place for you in the gay student group

now forming on the Orono campus.

MacNaughton, like so many gays and lesbians at the time, was not fully “out” about his sexual orientation. Feeling isolated, he wondered if this new club could serve as a safe space for him and others to share the friendship, stories, and life stresses of being gay.

Arriving for the meeting at Memorial Union on September 11, MacNaughton recalls his anxiety. “I went up and down the stairs to the meeting room three times before I dared to go in.”

But to his relief, he spotted a familiar face in the sparsely populated room: Sturgis Haskins, a graduate student and one of the meeting’s organizers. They were acquainted but until that moment neither student was aware that the other was gay.

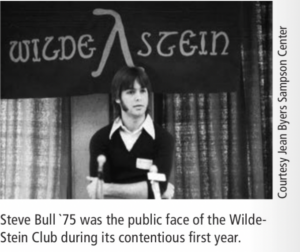

Six others joined Haskins and MacNaughton at that first meeting: co-organizers Karen Bye, Steve Bull ’75, and John Frank, all undergraduates; graduate students Dan Estes ’69 and John Noble ’70G, ’75 Ph.D.; and David Cadigan, a non-student and local activist. Together they founded the Wilde-Stein Club, dedicated “to fill[ing] the needs of the homosexual community at UMO [and] to creat[ing] a campus atmosphere where the Gay student can live in an open society free from repression and discrimination.”

Fifty years later, the club endures as Wilde Stein: Queer Straight Alliance, a name that reflects the organization’s evolution and growth in membership, gender diversity, and  social relevance. A 50th anniversary commemoration will take place in October as part of UMaine’s Homecoming Weekend.

social relevance. A 50th anniversary commemoration will take place in October as part of UMaine’s Homecoming Weekend.

The organization has come a long way from when the club’s very existence incited what one Maine newspaper described at the time as “one of the most bitter attacks on a minority group this state has ever seen.” The organization’s inaugural year — and one event in particular — today are widely recognized in Maine and beyond as historical markers in the ongoing civil rights struggle in the United States.

UNDERSTANDING THE TIMES

1973 was a year of deep social and political polarization, fueled in large part by the ongoing Vietnam War, the Watergate investigations, the Supreme Court’s Roe V. Wade decision, and the push for equal rights for women and Blacks.

Less attention was being paid to the nascent homosexual rights movement. Four years earlier, New York City police had raided The Stonewall Inn, a Greenwich Village nightclub popular among gays and lesbians. Patrons, angry about law enforcement’s routine harassment and use of force against them, rioted and protested for six days. Now historically referred to as the Stonewall Uprising, the clash is recognized as the genesis of the modern Gay Rights movement.

In Maine, a small Bangor-based group called Gay Support and Action was the only organization in the state actively advocating for gay and lesbian rights. That changed with the establishment of the Wilde-Stein Club, named in honor of gay literary figures Oscar Wilde and Gertrude Stein.

“We decided that we shall not be ignored any longer,” Karen Bye told the Maine Campus at the time. “We are going to educate this campus” through peer education, health counseling, social activity, and political advocacy.

The group met Friday evenings in the Union’s Coe Lounge. “[The room] had two sets of double doors with glass,” Steve Bull recalls. “People would go by and look in at us. It was like [being] at the zoo — we were on display.”

The club’s first social event, a dance, was held near campus at the end of the fall semester. As anticipated, the gathering raised eyebrows and drew a few vocal critics. But it would be the club’s next event that would trigger what remains the most contentious public controversy in UMaine history.

LIGHTING THE FIRE

Late in 1973, Wilde-Stein requested permission to rent part of Hilltop Commons during the spring semester in order to hold a “Maine Gay Conference.” The gathering, intended to attract attendees from around the state, would feature presentations and panel discussions about gay and lesbian rights, history, and health issues.

University officials were uncomfortable with the idea, as archival records reveal.

“When I first learned that there were plans for a statewide gay conference on the campus, I decided that I would quietly work to have it canceled or delayed,” UMaine President Howard Neville recounted in a letter to his boss, University System Chancellor Donald McNeil. Neville said he preferred “to oppose the conference and thereby send it to the courts for resolution unless I was directed to do otherwise by [McNeil] or by the Board.”

But that option was all but eliminated when, on January 16, a federal court ruled that the University of New Hampshire had unlawfully denied UNH’s Gay Students Organization (GSO) the right to hold functions on campus. “The GSO has the same right to be recognized, to use campus facilities, and to hold functions, social or otherwise, as every other [UNH student organization],” the landmark decision declared.

Emboldened by the UNH ruling and impatient with the university’s failure to act on its request, Wilde-Stein quickly announced its conference plans pending the university’s “final approval.” The club’s news release stated the conference would take place on April 20 and would be open to “Gay and interested non-Gay people alike” (which one news story paraphrased as “homosexuals and normal people”).

Neville, McNeil, and the Board of Trustees faced a dilemma: Should they permit the conference and risk a predictable and costly PR crisis? Or should they deny the club’s request and prepare for an equally predictable lawsuit and defeat in court?

After deliberating for five hours, trustees were guided by the university’s existing and permissive “Freedom of Speech and Assembly” policy. “Accordingly, we see no reason to deny any student group the right to meet on our University Campuses for lawful purposes in accordance with University policies.”

The conference would go forward.

OUTRAGE AND INSULTS

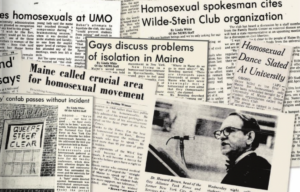

The board’s decision drew immediate backlash and resulted in Wilde-Stein’s conference becoming the dominant political topic in Maine.

“These homos are interested in recruiting new members,” Rev. Benjamin Bubar, leader of the fundamentalist Christian Civic League of Maine, told the Bangor Daily News. Unless it was blocked, the conference would contribute to what he claimed was greater Bangor’s reputation as “a hotbed of this kind of perverted activity.”

The Rev. Robert Gass of the Pentecostal Assembly of Bangor distributed to churches 40,000 copies of a form letter he wanted congregants to mail to state legislators calling on them to intervene. Like Bubar, he said he feared that the Bangor region could become “a mecca for homosexuals.”

The Rev. Robert Gass of the Pentecostal Assembly of Bangor distributed to churches 40,000 copies of a form letter he wanted congregants to mail to state legislators calling on them to intervene. Like Bubar, he said he feared that the Bangor region could become “a mecca for homosexuals.”

The Rev. Herman “Buddy” Frankland of Bangor Baptist Church went so far as to publish an open letter in Maine newspapers. Describing Wilde-Stein’s planned conference as a “conclave of perverts,” he urged the public to raise objections with state legislators — and to send money to his church to “help us” in this “life and death struggle.”

Maine newspapers were inundated with letters to the editor. Most submissions opposed Wilde-Stein and its conference. By Bull’s count, the Bangor Daily News alone published 82 letters in the three months leading up to the conference. A majority of those letters opposed the conference, frequently citing Scripture and sometimes referring to gays in homophobic terms. Most news editorials supported the trustees’ decision, as did the Maine Civil Liberties Union and several progressive religious leaders.

University officials and the Alumni Association also received scores of critical letters and phone messages. “No more donations so long as you sponsor homosexual clubs!”, one alumna wrote. “I just feel nauseated at the thought of Queers and Homos running free on the grounds of my alma mater!” wrote an alumnus. Relatively few respondents said they supported the university’s position.

“The letters to the editor really bothered me more than anything else,” club co-founder MacNaughton recalls. “These were people who vote, who may influence [and] represent what their community really thinks.”

The controversy spread beyond Maine, garnering national interest and media coverage as well. State Senate President Kenneth MacLeod ’47, a UMaine supporter and alumnus, appealed to trustees to reconsider their vote.

“I have received over 2,500 letters from Maine citizens expressing their opposition to the trustees’ decision,” he wrote. “It makes me apprehensive over the fate of future university bond issues and future university appropriations here in Augusta.”

In fact, a group of legislators attempted to blackmail trustees and block the conference by holding up the university system’s annual state appropriation. Floor debate sometimes turned vulgar, such as when veteran State Rep. Louis Jalbert grumbled that “a pack of queers” was jeopardizing the university’s funding.

Ultimately, the full legislature approved the money, with roughly 30 legislators dissenting. Later, System Chancellor McNeil would attempt to place the university administration’s experience in context.

“It made the Vietnam and Kent State furor look like fun and games,” McNeil told The Washington Post. “We never got as many letters on the Kent State protests as on this Wilde-Stein thing.” McNeil added that over time he believed people would better appreciate the university’s position. “It was a stand we had to take—free speech, free thought, human equality—and we took it.”

“SMALL HEROES”

By April, organizers had extended the conference to parts of three days (April 19-21) and rebranded it as the “Maine Gay Symposium.” The toxicity of public debate, combined with recognition of gays and lesbians as arguably the most marginalized minority group in U.S. society at the time, raised safety concerns on campus. Since many participants were still “closeted,” organizers asked news media not to identify, photograph, or film any conference attendee without first getting permission.

Three prominent gay activists agreed to participate in the conference: Nathalie Rockhill, national coordinator of the National Gay Task Force; Morty Manford, president of Gay Activists Alliance and a participant in the 1969 Stonewall Uprising; and former New York City Health Services Administrator Dr. Howard Brown.

“In those days, the fledgling LGBTQ movement was like a war and when a battle flared somewhere, troops went in,” Bull later explained. “We were the beneficiaries … Virtually every leading figure on the east coast in what was then called Gay Liberation came to Maine.”

Prior to the conference, Brown noted that he and other members of the national Gay Rights movement were surprised by the extent of hostility directed at Wilde-Stein and the university over the symposium.

“No other club in the country has experienced the opposition faced by the Wilde-Stein Club,” he stated. “I think members have been extremely courageous in asserting their rights,” calling the club’s leaders “small heroes” in the Gay Liberation movement.

Event organizers initially hoped to attract as many as 150 attendees. Instead, approximately 300 showed up. Bull, the conference chair, was buoyed by the turnout.

“I hope [the symposium] will be the beginning of an effective campaign for Gay Liberation in the state of Maine,” he said in his welcoming remarks. “Hopefully, through the efforts of everyone in this room today, the stereotype of Gay people will be smashed, and the discrimination and harassment of homosexuals ended.

“We are growing restless in our closets,” he declared. “We are here to demand what is rightfully ours.”

Attendance, energy, and the presence of a half-dozen security officers helped dissipate the fears of disruption. It became clear that most UMaine students were apathetic about the conference. There were just a few incidents: hundreds of anonymous homophobic flyers were distributed around campus; a small number of students posted signs in dormitory windows (“Queers Steer Clear,” read one); and a threatening banner (“The only good fag is a dead fag”) was draped across the black bear statue in front of Memorial Gym before it was spotted and removed by a campus official.

Along with speeches, the symposium featured a documentary film titled “How Hollywood Has Portrayed the Homosexual” as well as panels and break-out sessions on a variety of health, social, and political topics relevant to gays and lesbians. Social events, including a Saturday night dinner and dance, were well received.

The symposium was everything organizers had hoped for, and more.

LOOKING BACK

“’Gay’ Confab Passes Without Incident” professed one headline following the symposium’s conclusion. “After all the furor, the conference was pretty tame” stated another publication.

“Probably a lot of people — gay and straight — expected [the conference] to fail,” Dan MacNaughton offers. “When it didn’t, it probably made our goals seem more attainable, and this increased the political power of the group and what it represented.”

Bull says the club’s symposium laid the foundation for statewide action. “We immediately formed the Maine Gay Task Force (MGTF) to coordinate activism going forward,” he recalls. “We got [the first] gay rights plank passed at the state Democratic Party convention in Bangor. MGTF started a monthly newsletter in August [and] opened a public office on Middle Street in Portland in the summer of 1975.” MGTF also played an instrumental advocacy role in eliminating Maine’s laws against same-sex relations between consenting individuals, he adds.

Without question, Wilde-Stein’s influence on Maine is reflected by the much wider — but hardly universal — acceptance of LGBTQ individuals and the movement. Still, Bull and MacNaughton express concern about the current wave of political and religious attacks on members of the LGBTQ community.

“There are always ebbs and flows in social struggles,” Bull notes. “This deeply polarized society demands that we take nothing for granted and redouble our determination to fight.”

Bull, MacNaughton, and David Cadigan are the only Wilde-Stein founders who are still alive. Fifty years after their first meeting, all eight original members will be celebrated at fall events in Orono and Portland. Undoubtedly they will be remembered as the “courageous heroes” that Dr. Harold Brown once described them as.

Author’s note: Thanks to UMaine’s Fogler Library and the Jean Byers Sampson Center for Diversity in Maine at USM’s Glickman Library for providing access to their extensive archival collections about the Wilde-Stein Club and Maine’s LGBTQ movement.

Wilde Stein Club Celebrates 50th Anniversary

The Wilde Stein Club celebrated its 50th anniversary the week of October 10th as part of a University Maine Homecoming event at Fogler Library. The event started with the unveiling of “Those who will know Pride; The Start of UMaine’s Wilde Stein Club,” an exhibit at the Fogler Library commemorating 50 years of support and empowerment for the LGBTQIA+ community on campus.