E ditor’s note: Dennis Bailey, a former reporter and senior advisor to then-Gov. Angus King, Jr., is a public relations consultant who lives in Washington, D.C. In late September he was infected with the coronavirus, leading to a life-threatening bout with the illness and nearly a month in the hospital. This journal is adapted from the Facebook posts he wrote for his family and friends.

ditor’s note: Dennis Bailey, a former reporter and senior advisor to then-Gov. Angus King, Jr., is a public relations consultant who lives in Washington, D.C. In late September he was infected with the coronavirus, leading to a life-threatening bout with the illness and nearly a month in the hospital. This journal is adapted from the Facebook posts he wrote for his family and friends.

Sunday, Sept. 27: It was easy to tell myself that I couldn’t possibly have COVID. I was feeling all the typical symptoms — a fever of 102, weird body aches, scratchy throat — but I had been very careful to avoid it. I always wore a mask, kept my distance, washed my hands. Since I worked from my apartment, I didn’t really go anywhere except to the local markets to pick up groceries. I talked to my doctor who told me I was most likely experiencing some side effects from a flu shot that I had a few days before. But because I was planning a trip to Wyoming with some friends, I thought it would be a good idea to get tested for COVID, just in case.

Monday, Sept. 28: The test came back positive. It floored me. I wasn’t feeling terribly bad. Just a slight fever, some chills off and on. But over the next few days I completely lost my appetite (although I never lost my sense of smell or taste), and my oxygen level on the pulse oximeter I had bought at the start of the pandemic declined into the high 80s, while the norm is around 95%. Still, for most of the next week, I wasn’t incapacitated. I was still working at my computer and even managed to dance around the apartment to Prince one night while I was making dinner (that I didn’t eat). My doctor told me not to be too concerned, many people who get COVID experience mild symptoms and recover quickly. I was sure I was one of them.

Saturday, Oct. 3: Things had gone downhill. I just wasn’t feeling well. I was still running a slight fever, had diarrhea, and the scratchy throat had developed into a dry, persistent cough that gave me a headache. I had another talk with my doctor who recommended I head to the emergency room, so I called for an ambulance. The EMT who checked me out ultimately recommended against going to the hospital. “You’re not critical,” he said, “you’re talking in complete sentences, walking by yourself. We can take you, but I’m pretty sure they’ll just send you back.” So, I stayed.

Sunday, Oct. 4: I woke up feeling even worse. My oxygen level had dropped below 70%. (It turns out it’s one of the many strange side-effects of this disease, a low blood oxygen level that under normal circumstances would incapacitate someone but seems to leave COVID patients mostly functional. Doctors call it “happy hypoxia.”) Looking back on it, I think I was confused about the seriousness of my condition or what to do, even though I couldn’t tie my shoes without gasping for air. Fortunately, my good friend Phil (the lead guitarist in my band) was concerned and was on the phone calling hospitals and encouraging me to call an ambulance. He did it for me, and this time there was no argument. I was on the gurney and headed to the emergency room.

By the time I was admitted to Howard University Hospital, I realized this was serious. I could see it on the faces of the nurses and doctors treating me. They were pumping 100% oxygen through two masks, one into my nostrils and another covering my nose and mouth. Then I heard one of them say, “We need to get him to ICU.”

For the next several hours I laid in my bed while they wired me up to all kinds of monitors, an IV, took X-rays of my lungs and started taking blood samples. At one point, and I can’t recall exactly when, the doctor told me I qualified for some of the experimental treatments, but he needed my consent. Why not? I happily signed some papers and they quickly administered the entire suite of presidential cocktails — Remdesivir, antivirals, Dexamethasone (a steroid), even convalescent plasma.

But they wouldn’t let me eat or drink because they were pretty sure I would be intubated and put on a ventilator; my breathing was that bad. They needed an empty stomach.

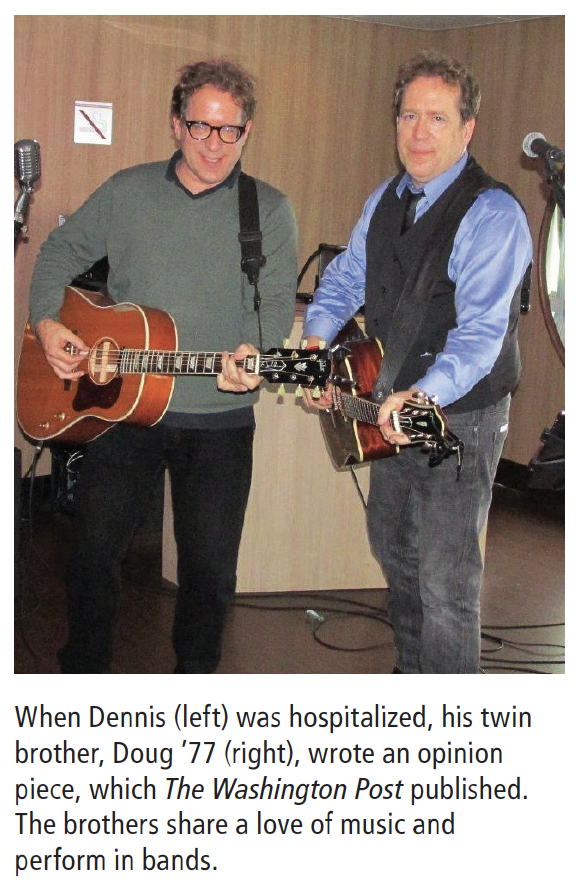

I called my twin brother Doug in Boston to give him the news, but I was coughing so bad I had to cut the call short. I texted to tell him I might be seeing Elvis soon, our little dark humor in the face of calamity. I could tell he was concerned and upset, and after he saw President Trump on the tube dismissing the seriousness of the pandemic, he did what any former journalist would do: penned a response that was published in The Washington Post. Go Doug.

Tuesday, Oct. 6: Today started on a high note. A full breakfast was served — eggs, sausage, muffin. Doctors were now satisfied that my O2 level was stable and it’s unlikely I’ll need to be on a ventilator (but I was still on two oxygen masks). Crisis averted.

Wednesday, Oct. 14: Almost two weeks in ICU. The scariest thing about this disease is not knowing. The knowledge base is evolving so doctors and nurses can’t answer basic questions. “Am I going to be OK?” “How long will this last?” The most common phrase I hear is, “It affects everyone differently.” Some people are sick for a few days and go home, others are in the hospital for more than a month, some don’t make it. So it’s a waiting game.

Also, it’s a solitary disease. My brother and daughter both asked if they should come to DC, but why? They can’t come into the ICU. I wouldn’t be able to see them or talk with them. I’m totally isolated, alone. It’s just another tragic consequence of this awful disease.

The other odd thing is that for the most part I’m not really in distress. There’s no pain. As long as the oxygen is pumping (and right now it’s at 70% flow) I’m fairly comfortable, able to watch TV, read, and listen to podcasts while my lungs slowly recover. The nurses come in almost every few hours to check my vitals, look for blood clots in my legs (another common side effect of the disease) and administer my cocktail of meds. Of course, they’re so heavily covered and masked that I have a hard time hearing what they’re telling me. Maybe it’s bad news, I’m never really sure. I joked with my brother that I was sure they were telling me my testicles were black. “No,” they said, “your test results are back.” Oh. Different.

The problem comes when I move around. Even rolling over or sitting up in bed exhausts me. After a few days I told the doctor I wanted to get up and walk around, but he said, “I don’t think you’re ready for that.” Not long after they moved me to a new room in ICU that had a commode (I had been suffering the indignity of a bedpan), I unhooked all the monitors and walked about two feet to the toilet. Instantly, I was out of breath and had to lunge for the oxygen mask to get my breathing back to normal. The doctor was right.

Friday, Oct. 16: I was told going in there would be days when progress would be slow or non-existent, or even backsliding. Today was one of those days.

It started last night. I watched the Trump-Biden town halls, some of the shows after, and turned in around midnight. Around 2 a.m. my alarms started going off. My pulse inexplicably shot up to around 160 bpm. There was no pain, but I was sweating profusely. They brought in an EKG and found my heart was out of rhythm. So they gave me potassium and some meds, and brought the pulse down a bit, around 140. I dealt with it the rest of the night, trying to get it under control, no sleep. They assured me that I was NOT having a heart attack, just off beat (which pretty much sums up my life).

Finally, around 11 this morning the cardiologist came in, asked a lot of questions, then suggested he should zap me with the paddles to get things back to normal. I didn’t like the sound of any of it, but with my heart racing at 150 bpm for like 10 hours straight, what choice did I have? This was not sustainable.

They brought in the whole cardiology team, about six nurses and doctors, plus others looking through the window from the nurses’ station. (This is a learning hospital, I guess I was today’s lecture.) I had the cardiologist walk me through the procedure several times. I wanted to know exactly what was going to happen, or supposed to happen, every detail. He was very patient and tried to get me to relax. They injected a pleasant sedative to keep me comfy and then attached the paddles. I asked the doc, “Have you ever lost anyone during this procedure?” He paused. “Well, not me personally.” WRONG ANSWER!

With everything and everyone in place, it was showtime. There was no countdown or “CLEAR” like on TV. He just threw a switch and it seemed like a small cannonball landed on my chest with a thud and lifted me off the sheets. Everyone turned to look up at The Machine That Goes Ping, and miraculously the pulse number went back to normal, around 80 bpm. Success. The show was over. Everyone filed out.

So how was your day?

Epilogue: After two weeks in the ICU, almost two weeks in recovery, and playing whack-a-mole with several other complications, I was finally discharged on Wednesday, Oct. 28. As I was leaving, one of my nurses said to me, “I’m glad you made it.” I said, “Was there any doubt?” “Welllll….” She said, “when you came in you were pretty sick.”

My story should in no way diminish the experience of so many others who’ve had it worse, not to mention the nearly 240,000 Americans who have died from the disease. But I’m far from out of the woods. I was brought home in an ambulance and convinced the EMTs that I could walk into my apartment building on my own. But by the time I went up the steps to the elevators I was winded and needed oxygen, like now. I have to learn to be patient, not one of my strong suits.

I came home and was quarantined for two weeks because I was still testing positive for COVID (normal, I was told). I still required regular oxygen, even had to sleep with it, but gradually weaned myself off it after about a month as my lungs cleared. I had to have surgery due to a blockage in my urinary tract that developed in the hospital and required me to wear a catheter for two months. The surgery was successful but my recovery is ongoing. And I’ve been outfitted with a temporary heart monitor as a precaution due to the cardiac event I suffered in the hospital. So far it looks like I’ve escaped any serious long-term symptoms that many COVID sufferers endure, but we’ll see.

If there’s one thing I’d recommend to people about avoiding COVID, along with all the usual — wear a mask, keep your distance, wash your hands, avoid crowds, etc. — it’s to get healthy. If you’re overweight, lose some pounds. If you smoke, stop. If you’re not managing your blood sugar, get a handle on it now. Get fit as possible because if you get this thing, you’re going to need all your resources to fight it. I was lucky. I was in reasonably good health, I work out regularly, no major underlying issues. But this thing doesn’t just attack your lungs, it takes on your heart, your kidneys, your bladder, all your organs. I don’t have any doubt that had I been in poor shape it would have complicated everything, and it was complicated enough.

But despite my overall condition, I was walking pretty close to the precipice those first few days. I knew. I could have coded at any moment. Seriously. I know getting fit is easier said than done. But trust me. If you get this thing — and anyone can — being in good health is the best way to have a fighting chance to beat it. M

An earlier version of this diary appeared in the Maine Sunday Telegram. Reprinted with permission.