GINA FERAZZI frantically loads her Ford Fusion for a 300-mile drive north from her home in Riverside, California, to Mammoth in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. She says good-bye to Charlie, her Goldendoodle, who sulks when she departs.

It’s November 19, 2020, the end of a typical week in Ferazzi’s life as a staff photographer f or the Los Angeles Times. She is on the road every day, having received her photo assignments in the morning or the night before.

or the Los Angeles Times. She is on the road every day, having received her photo assignments in the morning or the night before.

“I always keep a bag somewhat pack– ed,” she said from her car during the five-hour drive from Riverside to Mammoth to document the effects of the coronavirus pandemic on the ski industry.

Last week she was in Phoenix, reporting on dissent among supporters of Pres– ident Donald Trump over the results of the 2020 presidential election. Before that, she traveled to northern California reporting on the effects of the pandemic in Stockton and Lodi in the San Joaquin River Valley.

“This year is unique. Everything is COVID,” she said. “We have not been allowed in the office since February.”

As a journalism major in the Class of 1984 at the University of Maine, Ferazzi could not have imagined she would become a Pulitzer-Prize-winning photojournalist.

“Photography was a hobby,” she said, recalling how she converted a small closet into a darkroom when she was in the eighth grade. A native of Longmeadow, Massachusetts, Ferazzi had never been to Maine, but knew she wanted journalism and enrolled in the Department of Journalism and Broadcasting.

“I only took one photography course, but I didn’t go because it started at 3 o’clock, the same time as softball practice.” Her excellence in field hockey and softball earned Ferazzi a full scholarship for

her last two years of college. She still holds the record for five goals in one field hockey game.

“Women didn’t get scholarships then,” she said, explaining the thrill of being so honored as a student athlete in the 1980s. “Sports really took over,” she said of her years in Orono. The camaraderie among teammates during their hours together on the bus traveling to competitions throughout New England is a lingering memory.

HER CAREER BEGAN in 1984 at the Kennebec Journal in Augusta, Maine. “I might not have become a photojournalist had the KJ not been looking forwould become a Pulitzer-Prize-winning photojournalist.

“Photography was a hobby,” she said, recalling how she converted a small closet into a darkroom when she was in the eighth grade. A native of Longmeadow, Massachusetts, Ferazzi had never been to Maine, but knew she wanted journalism and enrolled in the Department of Journalism and Broadcasting.

“I only took one photography course, but I didn’t go because it started at 3 o’clock, the same time as softball practice.” Her excellence in field hockey and softball earned Ferazzi a full scholarship for her last two years of college. She still holds the record for five goals in one field hockey game.

“Women didn’t get scholarships then,” she said, explaining the thrill of being so honored as a student athlete in the 1980s. “Sports really took over,” she said of her years in Orono. The camaraderie among teammates during their hours together on the bus traveling to competitions throughout New England is a lingering memory.

HER CAREER BEGAN in 1984 at the Kennebec Journal in Augusta, Maine. “I might not have become a photojournalist had the KJ not been looking for a photographer,” she said. In 1986, she moved to the first color daily newspaper in Maine, the Lewiston Sun-Journal, where Jay Reiter was photo editor.

“I knew you were an exceptional photographer from the first time we talked,” Reiter told her recently, after viewing an online Riverside (Calif.) Museum of Art program featuring her work. “Seeing your body of work tonight just blew me away.” Reiter continued to help Ferazzi edit her portfolio and the two have stayed in touch over the years. “He was pretty hard on me, but I’ve appreciated it,” she said.

After four years in Lewiston, Ferazzi began to get antsy and decided to spread her wings. She accepted a position at the San Bernardino Sun in San Bernardino, California. Four years later, she was hired at the Los Angeles Times, where she has been a staff photographer since 1994.

In Maine she covered “a sport a day” and cruised for feature photos in communities where there was perhaps one homicide a year. In California, she has covered five mass shootings, wildfires, protests, floods, and now, COVID-19. She also has covered presidential campaigns, World Series baseball, Hurricane Katrina, and Winter Olympics in Japan, Salt Lake City, and Italy.

“In my car I carry flood gear, fire gear, riot gear, and now COVID gear,” she said. Fire gear includes wildland fire boots, Nomex pants, shirt, and jacket; N95 and KN95 masks; and goggles, which keep out tear gas during protests as well as smoke during fires. She added a bullet-proof vest to her riot gear, in time to cover the post-election protests, and is equipped to cover COVID stories with white head-to-toe Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), booties, masks, and face shields. For floods she has rubber boots and sometimes waders, rain covers for cameras, rain hat, Gore-Tex jacket, towels, and an umbrella.

“A day in my life can be simple or crazy,” she said. “There is something new every day. It’s my passion. I love going to work. It’s not work. It’s a challenge every day.”

Ferazzi is one of 21 LA Times photographers who work rotating shifts that can be stretched by the demands of a news event. Six photo editors begin making daily assignments at 6 a.m., and photographers are encouraged to generate their own ideas as well.

“Our editors are super-nice,” Ferazzi said. “They respect what we do and let us pursue what we’re good at. We all have freedom and respect from our editors.”

What Ferazzi is good at, according to Times Director of Photography Calvin Hom, is documentary news and sports. “She waits for the moment and always, always gets the photo,” he said, praising her professional demeanor. “She is very poised and calm under pressure. She doesn’t get flustered and has great self-control.” Whether covering the Olympics, college basketball, or breaking news, “she never misses the play,” he said of her ability to shoot the photo that tells the story.

“I’m always looking for moments,” Ferazzi said. She has learned to stay around after an event ends when some of the most poignant moments occur. “Sometimes you invade people’s space, and you have to respect that,” she said. “Respect is the most important thing you put into your camera.”

As she watched firefighters and healthcare workers evacuate residents of the Riverside Heights Healthcare Center in Jurupa Valley, California, Oct. 30, 2019, she wanted to capture the drama without violating privacy. Smoke nearly obscured the scene as the Hillside fire, fueled by dry brush and extreme Santa Ana wind, drew dangerously close to the facility.

“It was a situation I had never seen before. It was surreal,” she said. “I did not want to stick my camera in their faces, but I wanted to show how medical personnel were helping. I was trying to show they were in dangerous situations while respecting their dignity.” Her photo of a firefighter pushing a lady in a wheelchair won Second Place for Breaking News in the 2020 National Press Photographers Association Best of Photojournalism contest and First Place in the 62nd Annual Southern California Journalism Awards for News Photo.

IN OCTOBER 2003, she spent 11 days, working all night to cover another wild– fire propelled by the Santa Ana winds in San Bernardino. “My eyes were so swollen they looked like hot-dog buns,” she said, adding she sought relief by turning on the car air conditioning full blast.

Her pictures, including a man jumping across his swimming pool ahead of flames, were among the 20 images in a package that earned the LA Times metro and photo staff a 2004 Pulitzer Prize for Breaking News.

At 11:15 a. m. on December 3, 2015, Ferazzi received a call that a terrorist had opened fire at the Inland Regional Center in San Bernardino. She was on the scene at 11:45. Blocked by a police barricade, she knew she could get a good view of the center from an adjacent golf course she had played often. What she found on the fairway was a circle of evacuated employees holding hands and praying. She photographed the moment, sprinted back to her car and had just transmitted her photos to the newspaper when she heard sirens blaring and police cars leaving the scene.

“It was a very fluid situation,” she said. “You either get in right away or you don’t get in. I knew I needed to get in. So I jumped into my gray sedan and got into the caravan of police and detective cars.” Two miles from the center, law enforcement in SWAT gear descended on a neighborhood near an elementary school in pursuit of the gunman and his wife.

“I hunkered down by my car’s wheel well and started photographing the scene.” Her front-page photo of armed police poised to shoot was among those that helped the Times win a 2016 Pulitzer Prize for Breaking News.

“She was instrumental in our winning the award,” said Photo Director Hom. “She lived nearby and was one of the first to get to the scene,” he said, crediting her quick thinking and strategy.

“You have to be where the action is, and you have to plan an exit,” Ferazzi said. “You have to know your surroundings, be prepared with the lenses you need, and have a back-up plan.”

Following the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis in May 2020, Black Lives Matter protests for racial justice came close to her home in Riverside. Protected from tear gas by her “super-air-tight goggles,” she documented two types of protesters: the peaceful BLM group who dispersed at the curfew and a group that showed up late wearing cloth face masks, work gloves, and some with respirators. “They don’t like cops. When they arrive late with backpacks, knee pads, and first-aid packs, you know they’re up to no good.” Commenting on her own safety on such assignments, she said, “I will stay until it’s not worth my life.”

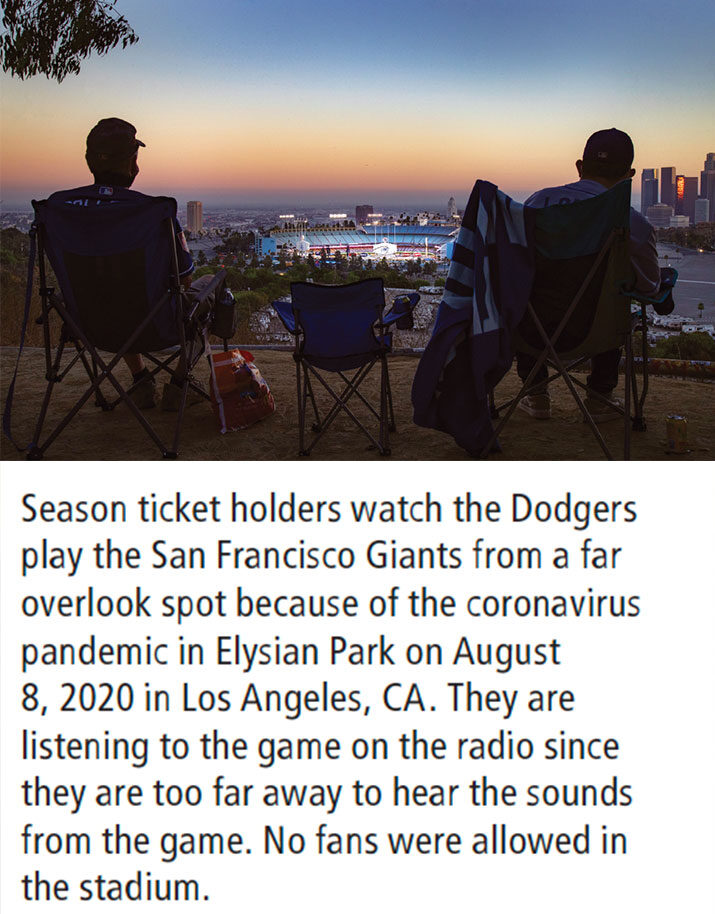

DURING THE 2020 coronavirus pandemic, Ferazzi has donned her head-to-toe PPE for hospital photographs, but much of her time is devoted to an assignment called “document your neighborhood.” She finds herself once again driving around looking for moments.

“My long years of looking for features in the state of Maine really helped me,” she said. She found barbers working outside, a hair salon in a tent, a drive-through graduation, and an evacuation of nursing home residents after nurses stopped coming to work for fear of infection.

Undaunted by the challenge of social distancing, she arranged with the subjects of indoor photos to photograph from outside through their windows — a ballet dancer practicing alone at home, a family making the best of a canceled prom by dancing together via Zoom, and three families that quarantined together in order to home school their eight children as a team.

“These are people who had to change their routines because of COVID,” Ferazzi said. She even found COVID moments at the Mammoth Mountain Ski Resort in November — blue marks in the snow at lift lines to make sure people ‘socially distanced’ and skiers and snowboarders wearing masks while traversing down the trails.

“Photojournalism is a great career,” Ferazzi said. “People appreciate what we’re doing and that makes it worth it in the end. I am not just a photographer, I’m a photojournalist,”

she said, stressing that journalism requires training in ethics and commitment to accuracy. While she laments the amount of misinformation in media, she is confident “journalism is always going to be here with a louder voice.” M