Civilians flee from Idlib toward the north to find safety inside Syria near the border with Turkey, Saturday, Feb. 15, 2020. Photo by quetions123 / Shutterstock.com

JANINE DI GIOVANNI HAS RISKED her life to tell the stories of ordinary people who have seen their families, homes, and countries ripped apart by war. So, as people around the world scrambled to protect themselves from the 2020 coronavirus, di Giovanni was thinking about those who could not do so.

“Isolation is for the privileged,” she said recently. “It presumes you have a room to stay in and water to wash your hands.” She worried about people in refugee camps who have neither, and for whom social distancing would be a cruel joke.

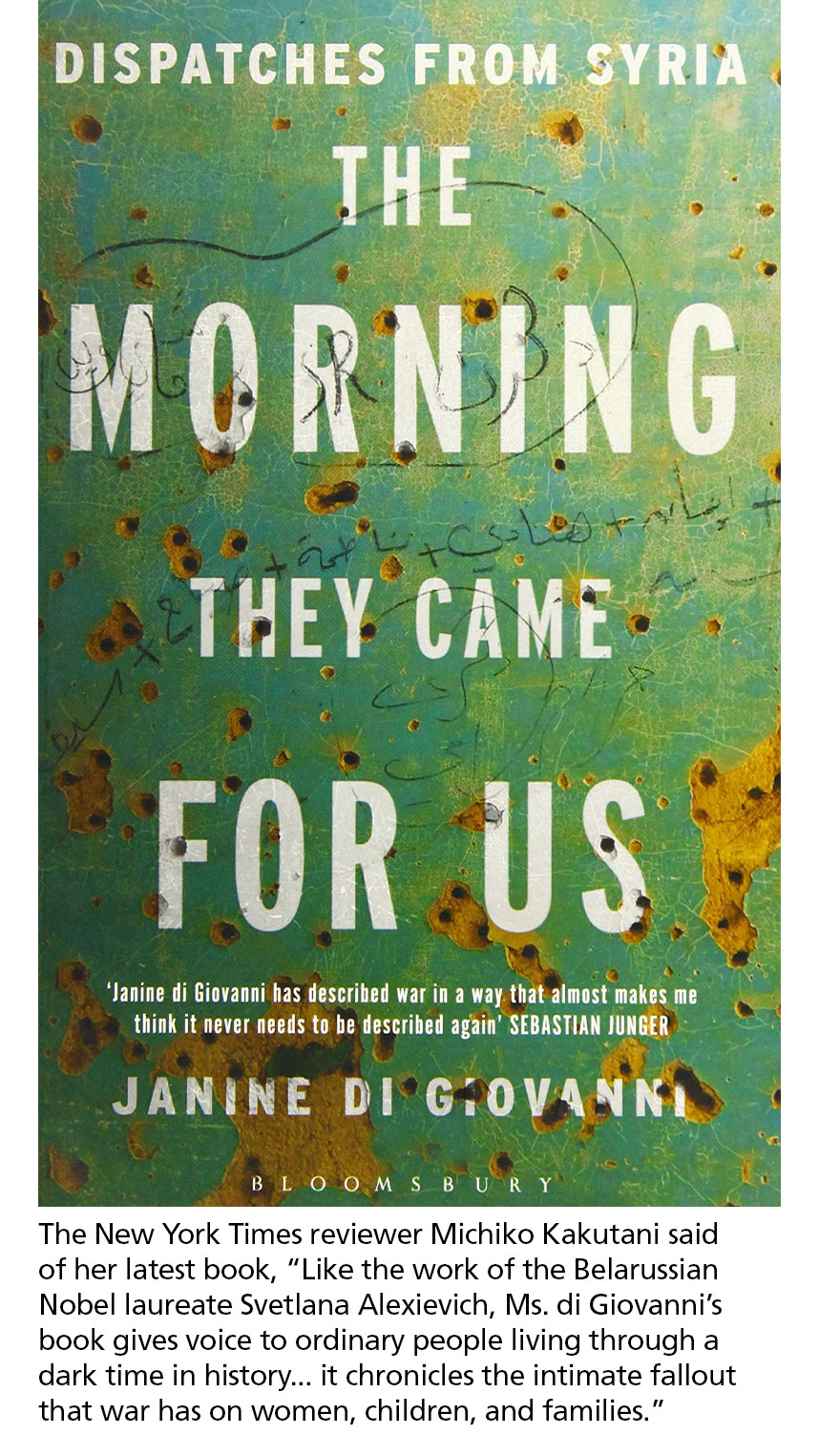

Her concern grows from three decades of front-line reporting in the Balkans, Africa, the Middle East, and Asia — reporting that has earned her numerous journalism and humanitarian awards. Hers are not the stories of a deadline news reporter frantic for a scoop to best the competition. Di Giovanni arranges to meet and sit down to talk with women and children, soldiers and generals, even the keeper of a morgue who records in a Book of the Dead what he can learn about the lives of people who are now corpses. “Over the years I have met hundreds of refugees from different kinds of war and different kinds of conflict and human disaster,” she writes in The Morning They Came for Us: Dispatches from Syria, published in 2016. “I know the velocity of war. In all the wars I have covered – including Bosnia, Iraq, Afghanistan, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Chechnya, Somalia, Kosovo, Libya, and more — the moments in which everything changes from normal to extremely abnormal share a quality.” She describes that juxtaposition of normal and abnormal with anecdotes: “I went to bed after dinner at a lavish Italian restaurant. When I woke up there was no telephone service and no radio broadcast in the capital; ‘rebels’ occupied the television station and flares shot through the sky. … This is how war starts.”

I connected with di Giovanni near the end of what was to be a two-week visit to France from her current home in New York City, where she is a Senior Fellow at the Yale Jackson Institute for Global Affairs and a Guggenheim Fellow. We agreed to talk when she returned to the U.S. That was March 14, 2020. Five days later, she emailed, “We’re in the middle of a pandemic and I’m escaping from Paris on the last train.” An interview for MAINE Alumni Magazine was the last thing on her mind.

Within a week, settled in an Alpine village of 30 people in the Vercors region of France with her son and ex-husband, she had already written a story about her experience that Vanity Fair published on March 25: “Letter from France: A War Correspondent’s Survival Mindset Shapes her Coronavirus Exile.

“I tried to remain calm,” she wrote of French President Emmanuel Macron’s warning that the country was “at war” with the virus. “War is something I know well. I operated in war zones, sometimes on autopilot, for three decades, mainly writing for Vanity Fair. I knew how to find my way out of a minefield and when to seek shelter during a bombing raid. I knew how to get through just about any checkpoint in wars in the Middle East, the Balkans, and Africa. Don’t make eye contact. Have your papers ready. Be polite but firm. Never get out of your car, especially if child soldiers wielding RPGs are aiming them at your heart.

“But an invisible enemy – an angry and stubborn virus whirling its way around the globe — was a new concept and one that terrified me beyond belief.”

I reached her by phone, April 2, from my 150-year-old house in northern Maine to her ex’s 350-year-old house in southeastern France, sharing some guilt about our respective safe havens. Having read her articles and books chronicling the unspeakable violence and destruction she has witnessed, I wanted to know the origins of her drive to put herself in harm’s way to portray the lives of people damaged both physically and emotionally by war.

“I think my real motivation was a hatred of bullies,” she replied. “When I was eight I beat up a much-older boy who had ripped up my brother’s homework. I broke his nose by swinging my backpack at his face after he was tormenting my brother. My brother was actually older than me, but wasn’t as good at standing up to bullies as I am. He died tragically young. So I guess part of my motivation is to go after the bad guys and not ever let them get away with it. Bullies need to be stood up to. That’s what I try to do.”

“She has been actively engaged since the late 1980s in telling stories that have – or should have – saved lives and relieved suffering,” said Steven Evans, currently chair of UMaine’s English department. “Her long-form journalism restores dignity and nuance to people, especially children and women, whose lives have been unduly reduced by the horrors to which they have been subjected.”

THE YOUNGEST OF seven children in an Italian-American family, di Giovanni grew up in Caldwell, NJ, an affluent suburb a half hour from New York City. She recalled receiving a scholarship from the local branch of the American Association of University Women. When she told the club’s representative she wanted to study journalism, the AAUW member, who happened to be from Maine, said, “You should go to Maine.”

“It was a shock, a lovely shock,” di Giovanni said of her introduction to the campus she had never visited. “But it was meant to be,” she concluded. At UMaine she formed strong friendships and decided she preferred creative writing to news reporting, shifting from journalism to earn a degree in English.

She honed her writing skills at the prestigious Iowa Writers Workshop, fueled by the doubts of Maine professors who said she was unlikely to be accepted. There she learned the discipline of writing every day and overcame the sting of rejection by submitting a story to The New Yorker every week.

Her weekly rejections taught her that “it doesn’t mean I’m not good enough. It’s just not right, or doesn’t fit the mix, for the magazine at the time. It’s never about you. That’s a lesson for anyone.”

Nevertheless, di Giovanni lacked the patience to pursue the traditional path of a young journalist working her way from intern to beat reporter and maybe someday an overseas assignment. She wanted to be a foreign correspondent, so she went to London and began freelancing. It was a period when the Berlin Wall came down, followed by the collapse of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia and civil wars in Africa. “I very quickly shifted my hat from being a writer to a journalist,” she said in a 2017 interview. In the late 1980s, di Giovanni met a woman who rekindled that fight against injustice ignited by bullies in a New Jersey schoolyard. On a visit to a Palestinian refugee camp, she met Felicia Langer, a German-Israeli Holocaust survivor and lawyer who defended Palestinians in military court. Her human rights activism provided a model for fighting injustice as an adult and inspired the type of narrative journalism that would become the hallmark of di Giovanni’s career.

“I had no mentor,” she told me, recalling hostility from both men and other women in the profession at that time. When she met Langer, she saw what she wanted to do with her life. “She lived a life of pure conviction for doing the right thing for people who had no access to justice.”

Di Giovanni wrote an article about Langer for a British newspaper titled “The Embattled Case of Felicia Langer.” It was so well received she was offered the opportunity to publish a book on her West Bank experiences during the Intifada. Against the Stranger: Lives in Occupied Territory launched her career as a foreign correspondent. She was 26. Di Giovanni wrote for The Times of London, The Spectator, The Daily Telegraph and other publications until she accepted a job as war correspondent for The Sunday Times in 1991. She was sent to cover the war in Bosnia where she witnessed the 1992 siege of the capital, Sarajevo, by Bosnian Serbs, the massacre of Muslim men and boys in Srebrenica and NATO airstrikes in 1995, and a 1998 war between Serbs and Albanian rebels in Kosovo.

“How different my life would have been had I never seen a mass grave or a truck with bodies, all dead, piled one on top of another, their skin changing from the softness of the living to the leathery skin of the dead. Or a torture cell with the incarcerated’s dying wish and last words of love to his family.”

“There was only so much I could physically do in one day, and when I did not, Catholic guilt preyed on me ferociously,” she wrote in 2010. “The worst was the knowledge that I could leave whenever I wanted to, and they could not. My friend Corinne kept reminding me I was not a social worker but a journalist. But for all of us living in that place, that time, it was impossible not to blur the lines.”

BOSNIA WAS JUST the beginning. In addition to her stories from the Balkans, she has portrayed the human cost of wars in more than a dozen countries in the Middle East, a dozen African nations, as well as Vietnam and East Timor. She and a photographer were the only western journalists to witness the fall of Grozny, the capital of Chechnya, Russia, and her documentation of war crimes has been used in criminal tribunals. She has written seven books and is working on an eighth about Christianity in the Middle East titled The Vanishing. Her 2012 TED talk, “What I Saw in the War,” has topped 1 million views on YouTube.

In 2013, the organization Action on Armed Violence named di Giovanni one of the 100 most influential people in the world of armed violence.

“I realized early on that life is short,” she said, recalling Thoreau’s declaration that he went to the woods to live deliberately and not find, when he came to die, that he had not lived. “I saw so many whose lives were cut short. They were alive one day; the next day they weren’t.”

UMaine’s Evans praised di Giovanni for “courage to travel as she has done, deliberately and repeatedly, into harm’s way, to listen patiently to what victims of siege and systematic rape and ethnic cleansing are, and are not, able to say to her about the atrocities they have experienced, and to shape those fragments of traumatic experience into narrative non-fiction.” Di Giovanni’s professional career includes numerous highlights: Guggenheim Fellow, Senior Fellow at Yale, a Columbia University professor of practice human rights, Murrow Press Fellow at the Council on Foreign Affairs, a former Ochberg Fellow at Columbia University School of Journalism, author of a half dozen books; a writer for The New York Times, Vanity Fair, Times of London, New Republic, National Geographic, Wall Street Journal, among others; winner of the National Magazine Award, two Amnesty International Awards, the Hay Medal for Prose, the Courage in Journalism Award, and, most recently, the American Academy of Arts and Letters 2020 Blake-Dodd Prize.

“And that is just the tip of the iceberg of her distinguished career in journalism,” wrote Paul Grosswiler, chair of UMaine’s Department of Communication and Journalism. He and Evans co-nominated di Giovanni for the UMaine Alumni Association’s Bernard Lown ‘42 Humanitarian Award, for which she was selected earlier this year. Grosswiler shared a quote by a Daily Telegraph book reviewer, who called her “one of our generation’s finest foreign correspondents.”

“My attitude is, I hope readers are upset by this [reporting on tragedy],” di Giovanni told the Paris Review in 2016. “That’s what I want to do, shock them out of their complacency. But I’m not doing it deliberately … I just told my readers what my reporting had told me. I didn’t exaggerate, I didn’t add anything. I didn’t have to.”

SHE SEES HER books as unembellished documents — “This is what happened” — examples of the oft-quoted observation that journalists write the first draft of history. She told me she would like to be remembered as one who amplified voices of those who faced injustice or state terror and were unable to defend themselves. “It is important to understand injustice on innocents because they are powerless,” she said. “There is nothing worse than being powerless, whether you are an abused woman in a domestic situation or a refugee who has nowhere to go. Someone has to be able to tell and amplify your story. I feel honored and privileged that in some cases, that person who got to tell the story was me.” Her teenage son, Luca, validated the impact of her work during one of their frequent walks in the mountains as they waited out the pandemic. He said, “Mum, you never give up your conviction. When you die, people won’t say, ‘She wrote a commercial book that made 20 million dollars.’ They will say, ‘Janine di Giovanni was a mother, a friend, and a writer who spent her life trying to help people.’”

Kathryn Olmstead, a retired member of UMaine’s Department of Communication and Journalism faculty, is a longtime writer, editor, and magazine publisher. She was inducted into the Maine Press Association Hall of Fame in 2018.