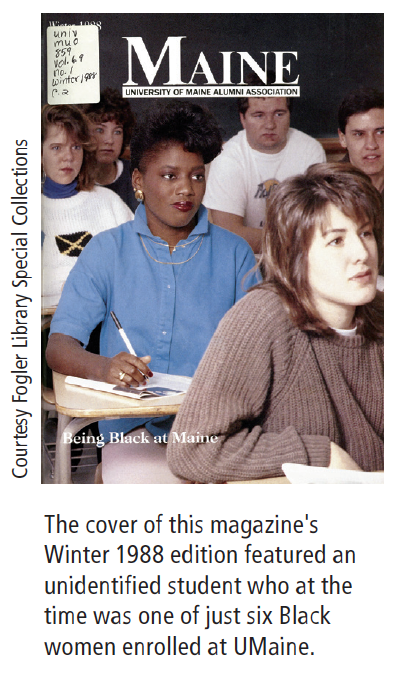

IN LATE 1987, JUNIOR Doug Dorsey was asked something that only 38 other students and two faculty members on campus could answer with any degree of authority:

“What’s it like to be Black at UMaine?”

The question, posed by a writer for this magazine, was prompted by the obvious — the ubiquitous whiteness of the student body and those who taught at the institution. The question was also timely: then-President Dale Lick had recently pledged to increase the university’s student diversity through a determined effort to recruit “minorities.” Their presence, he explained, would provide more “role models” on campus and help “broaden [student] perspectives.”

Dorsey, a business administration major and member of the football team, noted that Lick’s objective, while well-intentioned, would not be easily accomplished.

“It will take a long time to increase numbers of [Black] students at UM,” he said. “I won’t reap the benefits during my time here, but hopefully five or ten years down the road we may get up to at least five percent.

“I know it’s a slow process,” he continued, “but if it doesn’t get started now, it’ll never be reached.”

NEARLY 34 YEARS later, UMaine remains far short of Dorsey’s aspirational benchmark of five percent. During the fall 2020 semester, just two percent of all students — 219 — self-identified as Black, according to the university’s Office of Institutional Research and Assessment. (The total does not include students who self-identify as being of two or more races, one of which could include Black.)

Black student enrollment has remained at two percent of the university’s student population since the fall of 2012. However, the numbers and percent-ages of all students of color at UMaine from the U.S. grew during that period, reaching 12 percent (1,825) in the fall of 2020. $e largest historically underrepresented group, Hispanic/Latinx students from the U.S., made up more than one-quarter of that total.

Meanwhile, UMaine’s international student population totaled four percent in the fall 2020 semester. And while the experience of domestic students of color and international students are unique, they do share some life experiences. Together, they made up 16 percent of the UMaine student population in the fall 2020. That’s the fifth-lowest percentage of all land-grant universities in the U.S., trailing only South Dakota State, the University of New Hampshire, North Dakota State, and the University of Vermont.

Some could argue that 16 percent is an admirable, sufficient amount. After all, since Maine’s overall population is nearly 95 percent white, shouldn’t UMaine’s enrollment be reflective of the state?

Given the university’s mission and aspirations, the short response is no. This essay explains why.

Environment and Ecology

Driven in large part by matters of racial, societal, and economic inequality in the U.S., businesses and institutions large and small, public and private, are responding to the importance and value of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) to their organization’s objectives, employees, and clients. In most cases, these efforts take into account nine “dimensions” of diversity and inclusion in their operations: ability, age, ethnicity, sex and gender, race, religion, sexual orientation, socio-economic status, and nationality.

There are several reasons why encouraging and respecting diversity matters, both to UMaine and the state of Maine.

One factor is the gradual increase in recent years of the state of Maine’s racial and ethnic diversity. The influx of refugees from African nations, Mexico, and central America has increased the state’s ethnic populations, particularly in southern and central Maine. Many children of immigrant families have reached traditional college age, with those numbers expected to grow as young children get older. UMaine must be able to meet their educational needs while being supportive of their social and cultural traditions, just as the university does for its majority populations.

However, Maine’s educational, economic, and demographic needs and potential are bigger factors. With Maine’s population being the nation’s oldest as well as its whitest, the state’s future depends on its ability to educate and retain talent and attract businesses, industries, young people and families — critical elements for creating employment, developing and sustaining vibrant communities, and growing state and local tax bases.

And the state’s own history is a factor. It has a reputation for many impressive attributes, which make Maine an attractive place to visit, live, learn, work, and play for people of all ages, abilities, orientations, and identities. But its lack of racial and ethnic diversity is a liability, especially among younger people, employers, and prospective students and faculty members who are interested in more expansive cultural experiences and communities.

As the state’s largest and most programmatically diverse educational entity, UMaine must play a significant role in helping Maine achieve those objectives. But to position itself to contribute, it needs to address its environment (i.e., the conditions of its place and culture) and its ecology (the relationships and dynamics affecting the university’s people, resources, and systems).

According to a background paper prepared in 2019 by Dr. Robert Dana, UMaine’s vice president for student life and the university’s chief diversity officer, diverse cultures, experiences, and varying backgrounds are “critical to the vigorous discovery/learning processes that define a university.

“The challenge, for all of us, is to seek out diversity, which is the life-blood of a healthy intellectual environment, and to recruit and retain people who are traditionally underrepresented on our campus,” Dana wrote. “An inclusive environment is essential.”

However, recognizing what it takes and means to UMaine requires some explanation.

DEI and Higher Ed

“Diversity, equity, and inclusion are really rooted in understanding three main things,” explained Dr. Shontay Delalue `00, `03G, a scholar whose work explores diversity, equity, and inclusion. She recently joined Dartmouth College as its senior vice president and senior diversity officer.

“‘Diversity’ is composition — who’s on campus, who is not on campus, and [identifying] what people have been historically barred from higher education. And what recruitment strategies can we create to ensure that people from a variety of backgrounds have access to the institution.

“’Inclusion’ is [considering], once people from a variety of backgrounds are on campus, how do they have a sense of belonging?

How do we ensure that their voice is heard, that they feel empowered, and that they’re a valued member of the community?

“And ‘equity’ really looks at our policies, our procedures, and our practices. Are they updated in a way to create the kind of atmosphere where there’s fairness, where people can engage in the community and bring their full selves and not feel like they have to conform to a space that wasn’t originally designed for them?”

Accomplishing those objectives is no easy feat, as UMaine knows from experience. It faces obstacles related to the campus’s own traditions, culture, and historical approaches. As university leaders past and present have acknowledged, several efforts to make UMaine more inclusive have not succeeded, often falling victim to budget cuts or redirected institutional priorities.

Like so many colleges and universities, UMaine is known as a PWI – a predominantly white institution, founded in the mid- 19th century with the needs, futures, and perspectives of white people in mind. Despite societal changes and the intervention of lawmakers and courts, UMaine and a majority of land-grant universities remain PWIs, even though their missions address — and stakeholders consist of — individuals of all racial and ethnic identities.

Serving the needs of diverse constituents and preparing all students for life after college in the 21st century requires using an inclusive, multicultural lens to examine policies, practices, and priorities. That’s what UMaine President Joan Ferrini-Mundy called for in 2020 when she created the President’s Council on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. She appointed 33 individuals from UMaine and its regional campus in Machias to recommend specific actions that would, in Robert Dana’s words, make “inclusive excellence… foundational at the University.”

President’s Council on DEI

“Despite the dynamic nature of the challenges we face, UMaine retains important constant values: inclusive excellence at the core; unambiguous commitment to equity; and recognition of the centrality of diversity to a great university,” Ferrini-Mundy explained in September 2020. She cited three overarching questions that the President’s Council needed to pursue as part of its work.

“What are areas of systemic racism and other structural impediments to diversity, equity and inclusion at the University of Maine,” she posed. “And what policies and practices must be changed and reformed? In particular, what positions, realignments of responsibility and other changes [within the university] are most urgently needed?”

The President’s Council submitted its first report in December 2020. It presented 45 recommendations intended to “set the stage for significant progress in understanding and beginning to address [the university’s] DEI issues.” Three of them “are particularly urgent and important [and support] all of the additional recommendations”:

• Conduct a survey of the campus climate regarding DEI issues to identify current programs and to measure progress

• Establish an Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion under the direct leadership of a vice president or vice provost (The existing multicultural office is led by someone who reports to Dana.)

• Create, as a top university priority, an “immersive” physical and virtual university environment and ecology that reflect diversity and inclusivity

“These recommendations are a small first step,” the report acknowledges, citing as “most important” that these initial recommendations not only lead to action plans, but “that those plans are implemented in sustainable ways.”

Though it’s early in the process, Ferrini- Mundy’s commitment to addressing the university’s shortcomings on diversity, equity, and inclusion appear to be viewed on and o” campus as positive, authentic, and welcome.

“Our current president has undertaken huge initiatives as far as I’m concerned,” said John Bear Mitchell `96, `99G, a member of Penobscot Nation, the outreach and student development coordinator of UMaine’s Waban-aki Center, and a member of Ferrini-Mundy’s DEI council.

“In my tenure as a student and as an administrator at the University of Maine, this is the most aggressive stance I’ve seen any president ever take on inclusion — not just symbolic, but in policies and in the hard conversations,” he offered.

Inclusivity and Support

The college experience is filled with many unfamiliar challenges, expectations, and necessities, all of which affect most every student’s sense of confidence, belonging, and success.

Without question, plenty of white students feel isolated and unsupported at UMaine, at least in their early years. In some ways, that is true for white faculty members. $e university has many programs and policies in place to address and accommodate their educational, social, recreational, and health needs. In addition, there’s a plentiful pool of community members on and o” campus — many with similar backgrounds, affiliations, and life experiences — to whom they could turn for support and guidance.

And just as there are white students and faculty who confidently navigate the administrative, educational, and cultural aspects of campus life, there are members of UMaine’s underrepresented communities who have little to no trouble doing the same.

But unlike the large majority of UMaine students, many members of the university’s multiple, much-smaller underrepresented communities find the adjustments to the university community more challenging. They lack the numbers, support, and options that would help them find a sense of place and belonging.

Worse, for many, their sense of comfort and acceptance on campus is made more difficult by the color of their skin, the texture of their hair, the colloquial nature of their language and food preferences, and the ever-mindful history of being profiled, denied equal rights and protections, or targeted with hostility and violence because of their racial, ethnic, religious, gender identity and/or sexual orientation.

Those feelings among UMaine’s students, faculty, and alumni are very real. Examples were recently shared with MAINE Alumni Magazine through group discussions and individual interviews over Zoom with two dozen alumni of color. (See “Looking Back, Looking Forward” in this issue) Their voices help emphasize the various reasons why UMaine has had a difficult time attracting and retaining students and faculty from historically marginalized groups.

With low numbers, cultural obstacles, and the lack of resources, the presence on campus of underrepresented populations — notably, Black students and faculty — has failed to reach the aspirations expressed in 1987 by Dale Lick and Doug Dorsey. Recruitment and retention efforts of students and faculty have not been enough. Neither have UMaine’s focus on, and investment in, actions that by now could have earned it a reputation as a welcoming, supportive, and diverse community.

The report of the President’s Council on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion is likely the most comprehensive assessment of UMaine’s campus environment and ecology ever undertaken. Its findings and recommendations are based on extensive quantitative data, lived experiences, and subject matter experts.

Though members of UMaine’s underrepresented and underserved communities might find hope in the report’s recommendations, they are not the ones who can affect meaningful change. Nor should they bear the burden for doing so. That responsibility lies with board members, administrators, faculty, staff, alumni, and donors. Their actions and reactions will determine whether diversity, equity, and inclusiveness become ingrained in UMaine’s policies, practices, and behavioral values — and whether UMaine becomes truly welcoming and supportive of all who wish to be part of its community.

Maya Angelou, the late poet, author, and civil rights activist, famously stated, “When we know better, we do better.” In light of what Ferrini-Mundy has said and done regarding DEI, there should be no doubt that UMaine knows better. Now we all have to help the university do better. That’s what it will take for all alumni to feel that UMaine is indeed “the college of our hearts always.” M

John N. Diamond is the Alumni Association’s President and CEO

Click here to view the President’s Council on DEI.