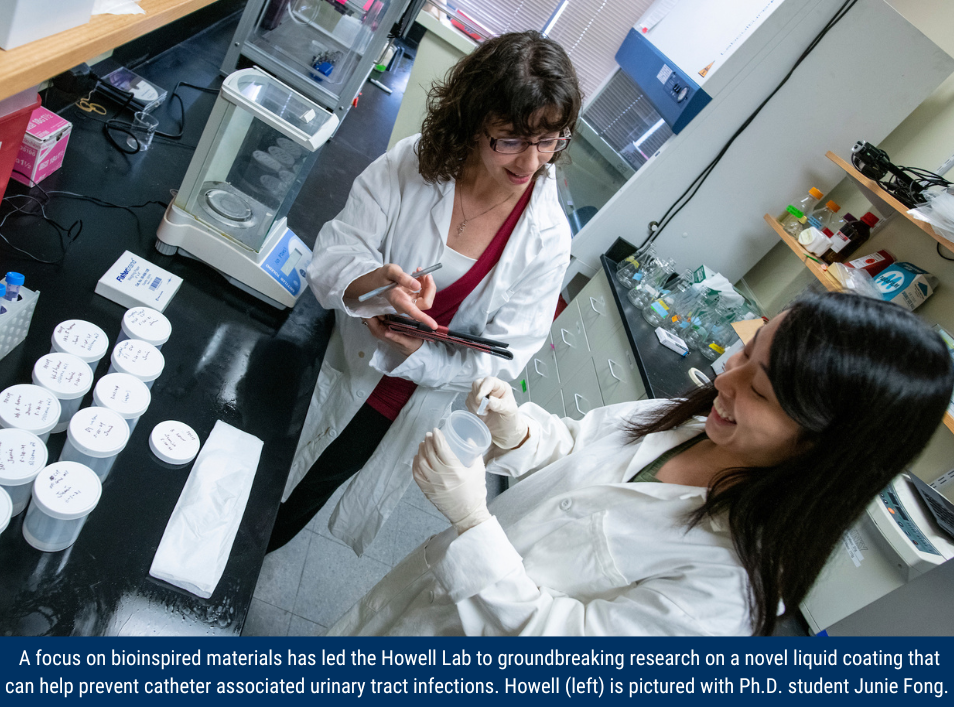

Black Bear alumni, faculty, staff, and students are among Maine’s most productive innovators and entrepreneurs. In this month’s column, we hear from Caitlin Howell ‘06, ‘08G, associate professor of biomedical engineering, a member of the University of Maine System Science Advisory Board, and research scientist at UMaine’s VEMI Lab. Howell, who studied biology at UMaine, received her Ph.D. from the University of Heidelberg, Germany, and completed post-doctoral work at Harvard University’s Wyss Institute, focuses on the intersection of biology, engineering, and materials science and shares an update on an NIH-funded project showing great promise for infection control.

—

Caitlin Howell: “The work in my lab is focused on bioinspired materials and has a lot of applications in both medicine and industry. We look to see how nature solves problems, and then take those ideas and try to apply them to human challenges. In particular, we work on developing materials and surfaces that can control biology, and can tell us information about cells or viruses or bacteria.

“A really relevant example of controlling biology is preventing infections. Bacteria attaching to surfaces, growing, and leading to infection is a big, big, big problem in a lot of areas, but particularly in medicine. We know that we are staring down an antibiotic resistance crisis, and in every year that passes we see more and more resistant bacteria and more people dying of resistant infections. Our bodies have beautiful, complex systems to control bacterial cells and keep them from causing trouble, and doctors and biologists are constantly learning more about how they work and the role they play in our health. In my lab, we work on the other side of those discoveries and try to build on those findings to create something that can be used in other areas.

“Catheter associated urinary tract infections are one of the most common infections in hospitals and long-term care facilities. They can affect anyone who needs a catheter for a medical procedure, and they often affect older adults, who tend to need catheters for extended periods of time. Every day that you have a catheter, you have a certain chance of getting an infection, and if you have a catheter in for 30 days, you have a 100 percent chance of getting an infection. One of the biggest projects in my lab right now, funded by the National Institutes of Health and in collaboration with biologist Ana Lidia Flores-Mireles at Notre Dame, is studying a novel liquid coating we’ve developed that can help stop these infections before they start. This is a discovery based on replicating the mobile, physical barrier property that our bodies naturally use to prevent bacteria from infecting our cells. In this application, we’re using a liquid coating that stops the adhesion of the proteins that the body releases in response to the catheter, which stick to the catheter surface and make it much easier for the bacteria to adhere and start growing.

“Just mimicking this one part of how nature controls bacteria led to jaw-dropping results. We were able to significantly reduce the number of bacteria in and around the catheters, but also to reduce the amount of bacteria that were spreading to the other organs in a living system. We’re taking part in UMaine’s I-Corps program this semester and pressing ahead to move that technology to market. It’s really exciting to be able to work on developing technologies that can really help the people of Maine, the U.S., and the world.”

NOTE: The “Innovators of UMaine” series is supported by a grant to the Alumni Association from the Maine Technology Institute.