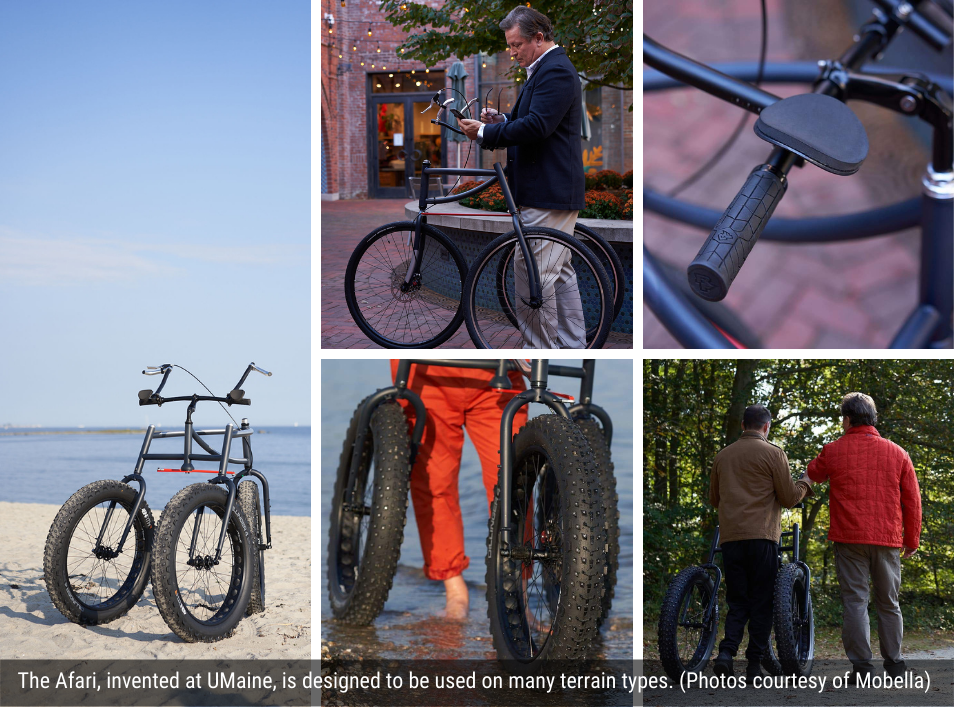

Black Bear alumni, faculty, staff, and students are among Maine’s most productive innovators and entrepreneurs. In this month’s column, the husband-and-wife team of Stephen Gilson and Elizabeth DePoy, both professors of interdisciplinary disability studies and social work at UMaine, provide updates on the adaptive mobility device they invented in 2013. Called the Afari, the sleek, three-wheeled device is designed to facilitate upright mobility and help users maintain balance while effortlessly navigating all kinds of terrain. Originally created by Gilson, DePoy, and UMaine professor of mechanical engineering Vincent Caccese so that DePoy could compete in a 5k race, the Afari technology has now been exclusively licensed for production and sale by Mobella, a company founded to commercialize stylish, functional mobility solutions for people with active lifestyles. Anything but your traditional walker, two versions of the Afari are now available for customers to purchase, and in 2017 the Afari was featured in the Access+Ability exhibition at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in Manhattan. The exhibition highlighted more than 70 innovative designs, exploring “how users and designers are expanding and adapting accessible products and solutions in ways previously unimaginable.” DePoy and Gilson, both of whom are dedicated to maintaining active lifestyles in spite of their own mobility challenges, look back on the Afari’s origins and ponder its future.

Stephen Gilson: “We are regularly active. We exercise every night. I have a bike that I can ride with one leg, and Liz has a quadricycle with multiple gears. Liz swims vigorously all the time, and I used to run marathons on crutches. It seemed to me that it might be fun for us to do a triathlon. We already had the swimming and the riding, but the difficulty for Liz, who has pretty involved ataxia, was translating running on a treadmill, where she could keep her balance pretty well, to running outside. To start, I convinced her to do a 5k race.”

Elizabeth DePoy: “And I listened, like a jerk.”

SG: “We started looking online just assuming that we could find something Liz could use to run, because she’s clearly not the only person with ataxia. We’ve both been in disability studies for a long time and we know that area, so we went to the typical places you might look, the U.S. Paralympic Committee, other sports folks nationally and internationally, trying to find out what people would use for that kind of erect mobility in a race. We couldn’t find anything that was going to meet her needs for functionally running in the road. The typical walker/rollator with the small wheels is like trying to maneuver a short shopping cart around, it isn’t safe or ergonomic, and it looks ugly. So we thought, why don’t we try to come up with something?”

ED: “If you go back to the research on the abandonment of mobility devices, even just for walking, you find that one of the major reasons people don’t use them is because they’re ugly. Just like any other person, I’m not going to use something I’m embarrassed to use. Another reason people abandon devices is because they don’t function. So the key became to build something that was upright, that functioned, and that looked good. We wanted something a person would be proud to use and not feel stigmatized. Instead of people looking at you saying ‘Oh, I feel so sorry for you,’ they’re saying ‘What is that? I wish I had one. Stephen and I are a good duo because he has a design background – I can think of what I want something to do and he can think about how it should look. And then Vince Caccese, the third member of our team, brings the engineering background to operationalize the idea and the images into a functional device.”

SG: “When we did it, there was not the intent to go commercial with it. It was research, and it was allowing us to continue to play. Liz ran the 5K with it, and I really didn’t expect anything more after that.”

ED: “The device that I ran with was a prototype and it was not especially comfortable, but it was a learning experience. That race was a needs assessment and a usability test, and we both learned from it about what needed to be done to make it better. We do a lot of theoretical work, and we wanted to have something that concretely illustrated the theory.”

SG: “After the race, it turned into a process of tinkering with the design, trying to improve the functionality, at first from a research standpoint. We did a fair amount of usability testing, we made different versions, and that led us in a new direction.”

ED: “Mobella is a great partner because they are marketing the Afari for design, for function, and for features. They don’t consider it a product for a segregated medical market but a product that someone would buy because they want it and not because they need it. It’s not about the body who uses it, but about its function and design.”

SG: “People’s needs change over the course of a lifetime and a lack of awareness about available equipment is a real issue. So, if you’re no longer able to ride a two-wheel bicycle, you may stop riding if you don’t know there are other options. Our vision for the Afari is to market it broadly so people understand how it can open up new possibilities in how they live their lives.”

ED: “This is the first device we sought to create, and that’s important because subsequent to that there were a number of other things, and we still are creating. We make products for people who want to be mobile. That’s not just about movement. It’s about continuing to live your life without having somebody tell you ‘Oh no, you can’t,’ or thinking ‘Oh no, I can’t.’ If you are a typical shopper, you have a choice of what product you want to buy, what you want it to look like. Everybody should have that choice.”

NOTE: The “Innovators of UMaine” series is supported by a grant to the Alumni Association from the Maine Technology Institute.